It was the hottest ticket in Madison for decades.

Long before the rise of the Wisconsin basketball team in the late ’90s — culminating in a Final Four finish in 2000 — the biggest crowds at the Field House belonged to the Wisconsin boxing team.

In the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, Madison had the opportunity to host some of the best young boxers to ever grace the ring, winning eight national championships in 27 years as an official school sport.

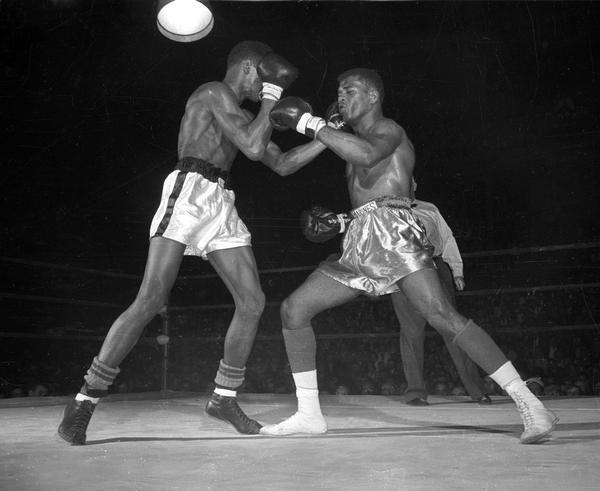

But it was perhaps the Pan American Amateur Boxing Trials in 1959 that brought the greatest boxer the Field House has ever seen in the form of a 178-pound, 17-year-old high school student: Cassius Clay.

Traveling a long way from his hometown of Louisville, Ky., Clay was one of the best young prospects in the sport. A Madison sports reporter, Henry McCormick, described the amateur boxer upon arriving in Madison as “a fine-looking youngster … rangy, long-muscled and pleasant-faced.”

While Cassius Clay — who changed his name to Muhammed Ali in 1964 — would go down in history as one of the most successful boxers to ever fight, his time in Madison might be remembered as one of the few blemishes in an otherwise spotless career.

Coming in as a hot-headed, cocky teenager in the eyes of famous Wisconsin boxing coach John Walsh, who officiated the Pan American Trials, Clay had already begun to build a reputation as a boxer on the rise. His 34-bout winning streak when he arrived in Madison April 27, 1959 largely did the talking for him. The Wisconsin State Journal listed him as “one of the United States’ brightest hopes for an Olympic berth” the following year in the 1960 Olympics in Rome.

As an event, the Pan American Trials at the Field House captivated a city. Tickets cost just $1 for a reserved seat (just one penny less than a gallon of milk in 1959) and ringside seats went for $1.50.

Clay made a show of it.

He dispatched fighter after fighter, including Leroy Bogar from Minneapolis in the semifinals by a technical knockout, all the while wowing the 2,324 spectators and reporters watching with his ability to lay blow after blow on his outclassed opponents.

According to McCormick, it only took a “quick sporting of brown gloves and Bogar was on the canvas.” Moments later, a “flashing combo by Clay almost put Bogar through the ropes.” That fight was ended soon after for fear of what might happen to Bogar if the bout continued.

Clay glided into the championship bout with ease, but then came Amos Johnson.

The 25-year-old Johnson was a marine and a southpaw with quick feet in the ring, who would eventually finish with an impressive 63-2 amateur record when he turned pro less than a year later.

And yet, despite the eight-year age gap, Clay was the heavy favorite. After all, Clay’s unbeaten stretch had swelled to 36. What would make this fight any different from the others?

Throughout the first round, both boxers held their own, finishing in a virtual tie — although the officials gave Clay the point.

But as the fight wore on, Clay struggled to defend Johnson’s devastating left hook.

With each crashing blow to his midsection from Johnson’s unconventional left-handed style, Clay began to fall behind. By the fight’s end, Clay had lost by a close 2-1 decision, his first loss in 37 tries.

Johnson would go on to compete in that year’s Pan-American Championships in Chicago, while Clay would be sent home empty-handed for the time being, with a bit of humility to boot.

Local sports personality Randy Coughlin, who had become famous in Madison for his knack for predicting sports outcomes, wasted no time in chastising the young boxer for his lack of defense in the Wisconsin State Journal a day later in his weekly “Roundy Says…” column.

“When Clay gets better on defense, brother he will be hard to beat,” Coughlin wrote.

Whether or not that criticism ever made it to Clay after his disastrous defeat is unknown, but Coughlin was right once again.

Five years and zero losses later, Clay was crowned the 1964 heavyweight champion of the world.

[Photo courtesy of UW Archives]