Last week, The Daily Cardinal published an editorial decrying several campus-area bar owners’ decision to remove many of today’s most popular hip-hop artists from their TouchTones players.

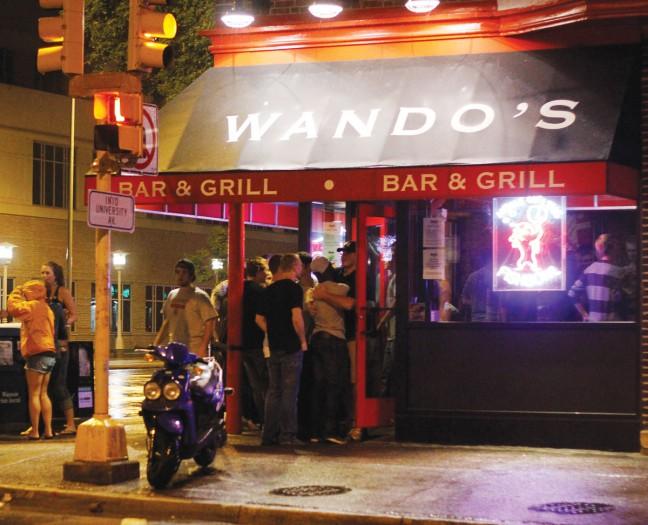

The piece eloquently outlined how even though none of the bar owners, including the owners of Wando’s, Chaser’s and Double U, specifically stated that they removed hip hop from the music options available to patrons because they don’t like black people, the implicit message is clear.

While the piece was beautifully written and spot-on, I’m not here to write about it. Instead, I want to address the backlash I’ve seen in response to it.

When the article was published, I saw it shared multiple times on social media, with several users commenting that it’s unfair to accuse these bar owners of being racist when there’s no evidence they hate any particular race and that accusations of racism aren’t something to be thrown around lightly.

One look in the comments section under the piece reveals many comments stating there is no reason to assume censoring hip-hop from a bar’s TouchTones player has anything to do with race or racism.

This is an argument I hear often, applied to defend racism in many different contexts. This apparent confusion about the definition and scope of racism has potentially huge implications, because, after all, many policies and acts throughout history have unfairly disadvantaged racial minorities without stating any explicitly racist intentions.

This “no hip-hop” policy is clearly targeting black people and black culture.

Even Jay Wando, one of the bar owners who responded to a request for comment on the matter, said the songs were removed “to keep out a bad crowd.” It is quite a stretch to imply that hip-hop music, a key part of black culture, should be banned because it is more likely to attract a rowdy crowd while maintaining that this decision does not imply that black culture itself is dangerous and rowdy.

Whether its intention is to discriminate against people of color or not, the policy will prevent many black people from feeling welcome in campus-area bars.

This issue, however, is not limited to the exclusion of hip-hop music. Many campus-area bars, including Wando’s, Whiskey Jack’s, Logan’s and Monday’s, enforce dress codes. Some of the most common wardrobe restrictions include plain white or “overly long” t-shirts, “overly baggy,” saggy, large or long clothes, long hats that are cocked to the side, do-rags and bandannas.

While those defending Wando and other bar owners are right when they say that racism is a serious issue, it’s even more important to realize that a policy doesn’t have to explicitly say it’s meant to discriminate against minorities for it to successfully do just that.

This isn’t the first time the University of Wisconsin and the nightlife near campus has been criticized for being a toxic environment for minority students. UW has been unsuccessfully trying to create a more inclusive campus for years.

As the piece in The Daily Cardinal pointed out, University Health Services’ 2015 Color of Drinking Survey shows 48 percent of students of color said they experienced microaggressions from intoxicated UW students and 40 percent of these students said they avoid the drinking culture in specific areas of campus such as Langdon and State Street.

It’s important to recognize that almost all of the most harmful instances of racism hurting minorities in this country haven’t been from individuals saying the n-word: it’s been policies that purposely disbar black and brown people. When bars makes their policy “no white t’s, no durags, no rap music,” it’s clear that they are trying to make rules to keep out a certain kind of person.

Saying you don’t want “the kind of people who wear durags or baggy white t-shirts or listen to hip hop” because they “draw a rowdy crowd” is about as close to clear-cut discrimination as you can legally get in a city where blatantly saying “no black people” is illegal.

UW and the larger Madison community simply cannot continue to ignore aspects of our community that are hurting our black and brown neighbors on the premise that they are “not meant to be racist.” In many cases, if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.

While “throwing around the word racist is dangerous,” refusing to call clearly racist things racist simply because they aren’t labeled as such is infinitely more dangerous. Doing so has prevented progress and gotten black and brown people killed since the birth of this nation.

Julia O’Donnell (julesyann19@gmail.com) is a senior majoring in journalism and strategic communication.