Wisconsinites can now dial 988 to be connected with a 24/7 crisis counselor. This number, the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, is the new name for the 2005 National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline launched July 16 as an effort by Wisconsin’s Suicide and Crisis Lifeline in conjunction with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to streamline crisis resources, according to the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Here’s how it works — Wisconsinites can contact the 988 Lifeline by call, text or the online chat feature. Next, the person will receive a response with options for Spanish speakers or veterans. Then, the caller will be connected with a counselor.

From there, most callers receive support and de-escalation help along with local referrals. If the counselor feels the caller poses a high concern of imminent risk of self or others, that person will receive a required wellness check from law enforcement. If the counselor feels the caller poses an imminent risk to themselves or others, they will receive a medical response along with required emergency law enforcement, according to the Crisis Services website.

If a call, text or chat message is not answered by the Green Bay crisis center, it will roll over to a national backup system, according to Spectrum News. But the goal is for Wisconsin-based counselors to be on the receiving end as much as possible because they are most knowledgable about local communities and resources.

The push for an easier-to-remember lifeline number stems from the fact that the majority of mental health emergency calls are currently dialed to 911. But most officers are not trained to address these emergencies, Wisconsin Department of Health Services crisis services coordinator Caroline Crehan Neumann said.

As a result, the police response can be — and often is — traumatic for callers. The connection between mental health emergencies and law enforcement currently serves to stigmatize mental illness, Neumann said. By doing so, people are further pushed away from accessing mental health resources that would alleviate their struggle.

Though a response by law enforcement is necessary in cases where an individual is at risk of hurting themselves or others, Neumann said, this does not apply to the majority of callers.

“We don’t want law enforcement to handle these situations [and] law enforcement does not want to handle these situations,” Neumann said.

Nationwide, the vast majority (98%) of those who utilize the free and confidential support system do not require emergency help, according to SAMHSA. Instead, trained crisis center counselors are able to provide relief for almost all who call the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline.

Ultimately, Neumann said the goal of the number change is to work toward 988 becoming as synonymous with mental health services as 911 is for fire and police services and, eventually, create a separation between the two services.

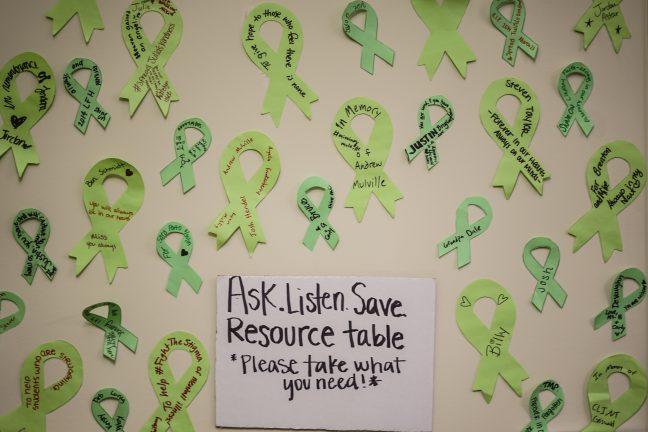

The transition to three digits was also an effort to increase awareness about the lifeline and its extensive mental health resources, according to SAMHSA.

According to Neumann, the publicity surrounding the number change has been instrumental in accomplishing this goal. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund, this is especially the case for young adults who, after experiencing emotional distress and social anxiety from the COVID-19 pandemic, are now entering the workforce.

While UW promotes its own mental health resources, the push by SAMSHA to extend mental health access makes crisis resources available to students and will help students once they leave campus.

“While I think that UW-Madison does a good job of promoting mental health services offered through UHS, I think a lot of students graduate without an understanding of how to access mental health resources outside of a campus environment,” UW junior Jenna Truck said.

The bipartisan National Suicide Hotline Designation Act, created by Sen. Tammy Baldwin and passed by Congress in 2020, brought the 988 Lifeline to fruition.

In addition to a number change, the lifeline also received a $1.7 million federal grant that has been used to hire more counselors and expand the call center, according to Wisconsin Public Radio. This was especially necessary as the number of calls to Wisconsin’s lifeline received over 4,400 calls in its first month of operation, according to the Green Bay Press Gazette.

In the future, however, Neumann aspires to see the Suicide and Crisis lifeline combined with other needed mental health services.

Wisconsin currently employs crisis mobile teams to provide in-person visits by a mental health professional, Neumann said. These teams are not available 24 hours a day nor seven days a week. Immediate in-patient treatment is likely to be acquired only in a hospital setting, even if an individual is assisted by a crisis mobile team, Neumann said.

Neumann and other mental health advocates are therefore striving for a streamlined response to mental health crises — one that would fuse together the process of calling, receiving in-person assistance and, if needed, a place to go outside of the caller’s residence.