CONTENT WARNING: This article contains a graphic image which may be disturbing to some readers.

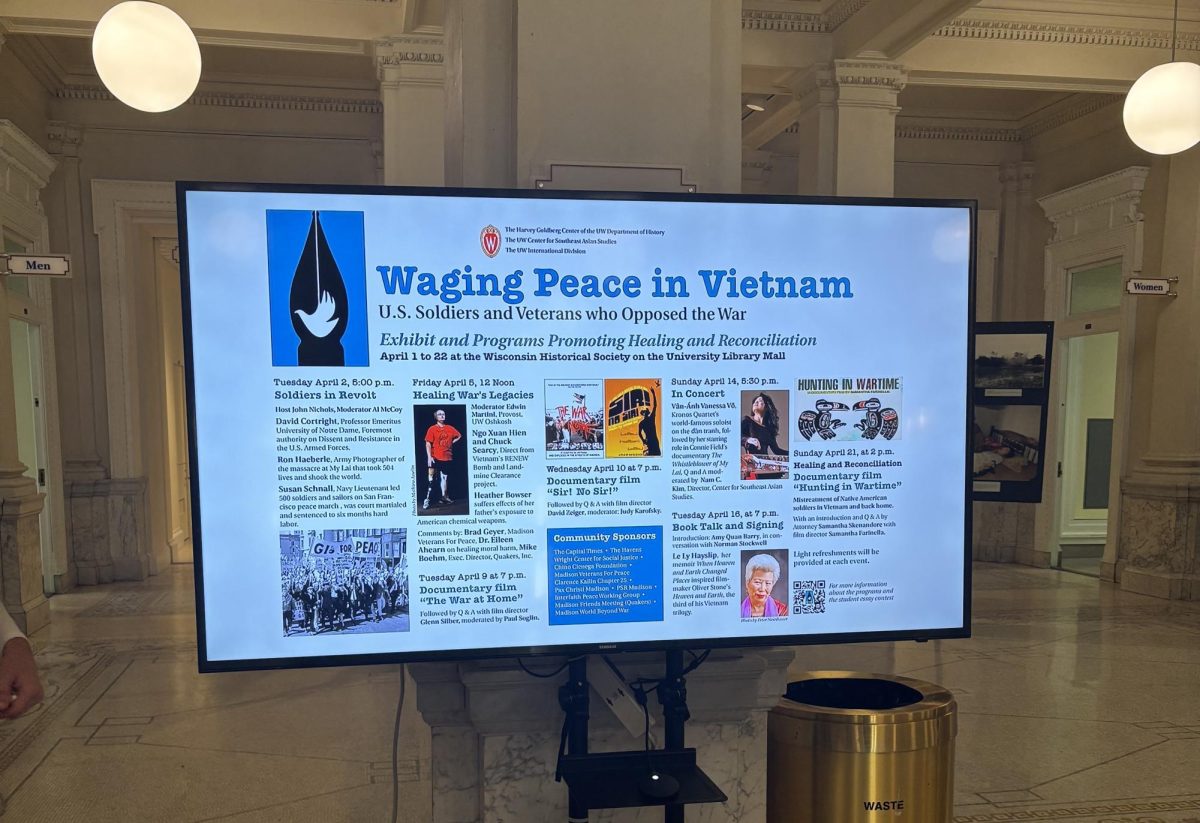

The Wisconsin Historical Society is hosting “Waging Peace in Vietnam” — a traveling exhibit that collects historical records of the anti-war movement during the Vietnam War — through April 22, according to the exhibit website. The exhibit focuses on the G.I. movement — a retaliation by active duty American soldiers against the United States government’s involvement in the Vietnam War.

Former Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee member and Executive Director of “Waging Peace in Vietnam” Ron Carver said the exhibit was created eight years ago to to highlight the anti-war movement inside the military — not as a result of young people who did not want to be drafted, but by people who enlisted to be patriotic, then arrived in Vietnam and saw firsthand the reality of violence for which the U.S. was responsible.

“There aren’t many people aware today of an anti-war movement within the military during the Vietnam War,” Carver said. “Those who are aware, a lot of them assume that this was the young folks who were drafted against their will and were disgruntled the whole time. No, this is made up of folks who turned against the war. And because they felt betrayed, when they realized what the war was … they were very passionate about building this anti-war movement within the military.”

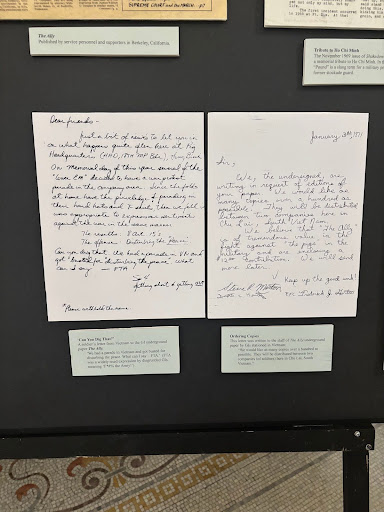

The exhibit has information about G.I. coffeehouses, which were made to rally opposition to the Vietnam war and serve as an anti-war sentiment to the U.S. military. In another form of protest, the exhibit displays testimony from Vietnam war soldiers, revealing anti-war sentiments that were common at the time.

Two letters that are part of the exhibit come from American soldiers who took part in protest parades in Vietnam. One of the letters — titled “Can You Dig That?” — was written by an American soldier expressing feelings against the U.S. army after a parade he participated in was condemned for disturbing the peace. The unnamed solider signed the letter with “F.T.A.,” the acronym soldiers used to shorten “fuck the army.”

A companion book to the exhibit, also titled “Waging Peace in Vietnam,” compiles firsthand accounts, newspapers, photos and other historical materials about anti-war activity originating within the U.S. Army. Carver edited the book with David Cortright and Barbara Doherty, and the work has since been translated into Vietnamese.

“I think that the other thing to know is that we dedicate the book to science and those killed and morally injured on both sides,” Carver said.

Today, there are still hundreds of thousands of small, unexploded devices in Vietnam, according to Carver. A replica of one of these explosives is included in the exhibit.

Vietnam War veteran Chuck Searcy travels to speak at the exhibit, according to Carver. Searcy founded Project RENEW in 2001, a non-profit that works to address the legacies of the Vietnam War in Vietnam through education, healthcare and financial support. RENEW works as a comprehensive mine action organization to educate Vietnamese citizens about ongoing mine risks, according to the RENEW website.

Searcy said he opposes not just the war in Vietnam, but subsequent wars, criticizing the United States’ patterns of violence.

“It’s not mistakes, it’s a methodology,” Searcy said.

Vietnam War veteran and former combat photographer Ron Haeberle played a pivotal role in bringing this violence to light. At the exhibit, Haeberle shares photographs during his station in Vietnam, which have since become some of the most important records documenting the Vietnam War and fueling the anti-war movement, according to Britannica. One of the photos included in the exhibit is a famous image captured in My Lai, Vietnam, depicting the aftermath of the U.S. Army’s massacre of 504 unarmed Vietnamese civilians. Plain Dealer and LIFE Magazine published many of Haeberle’s photos, leaving the public stunned by the violence.

Award-winning author and philanthropist Le Ly Hayslip has witnessed some of this violence firsthand, growing up in Vietnam during the war. Hayslip will visit the Wisconsin Historical Society Tuesday, April 16 at 7 p.m. to give a book talk about one of her memoirs, “When Heaven and Earth Changed Places,” which recounts her childhood experiences during the Vietnam-American War. Her original work, published in 1989, was adapted into the 1993 film “Heaven and Earth,” directed by Oliver Stone.

Hayslip was just 10 years old when she had to stop attending school due to the war, placing major barriers between her and a formal education. The impacts of the Vietnam War have left her generation with disproportionately low levels of formal schooling compared to subsequent generations, Hayslip said.

“No more schooling, no more teachers,” Hayslip said. “The teachers and future leaders died so we didn’t have anybody to teach us and that’s when I stopped going to school.”

Hayslip later went on to become the founder of two humanitarian organizations, Global Village Foundation and The East Meets West Foundation, which both work to bring relief, education and development resources to communities in Vietnam devastated by the long-term impacts of war.

Carver said he is astonished by the reach of the exhibit, having toured 25 universities in the U.S. and Vietnam, including Columbia University, University of Southern California and now, the University of Wisconsin. But coming to Madison is a particularly noteworthy trip, due the Wisconsin Historical Society’s highly extensive G.I. press collection, according to Carver.

“We’re all excited about [the exhibit] coming to Madison because there’s so much that’s originated from the Wisconsin Historical Society,” Carver said. “There were no photographs of sometimes hundreds, sometimes thousands of soldiers protesting in Vietnam, there’s no photograph of that. The fact that we got proof of it happening from the historical society website is significant.”