Note: This story uses person-first language (“people with disabilities”) and identity-first language (“disabled people”), per the mixed use in various interviews. Please note that people may prefer either term or different terms.

With a research expenditure of over $1 billion annually, it is no surprise the University of Wisconsin-Madison ranks 8th in the nation in research output. Of course, providing proper training is vital to creating a safe space for all researchers. But for people with disabilities who require additional accommodations, access to equitable resources in labs is limited and most lab spaces are not made to meet these needs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act “prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in all areas of public life, including jobs [and] schools.” In reality, massive barriers still exist, making participation extremely difficult for people with disabilities, especially in STEM.

McBurney Center disability program aide Katie Sullivan, who studies communication sciences and disorders and health promotion and equity, sees these barriers all around her.

“Disabled and chronically ill students are wholly underrepresented in STEM,” Sullivan said. “Having a disability and trying to work in STEM is highly stigmatized because there’s this notion that if you’re disabled, you’re not cut out to work in medicine or work in research or be involved in science.”

Recently, in 2021 the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that only 5.5% of men and women in life, physical and social science, architecture, engineering, computer and mathematical occupations had disabilities. And the National Institute of Health found that between 1999 and 2019, the percentage of people with disabilities in STEM grew a meager 3%, from 6% to 9%.

Much of the disparity stems from access to postsecondary education. There is a large discrepancy between those with disabilities and those without who have completed a bachelor’s degree. In early 2022, of people aged 25 and older with a disability, only 21.1% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, according to BLS. Nearly double the amount without a disability completed at least a bachelor’s degree, according to BLS.

At UW, students with registered disabilities can apply for accommodations provided by the McBurney Disability Resource Center. For many, the center provides extended time and smaller groups for testing, advanced access to course materials and adaptive technology to help with note-taking, according to Sullivan. Covering such a broad range of services is critical as McBurney supports over 3,600 students in differing areas of study.

While McBurney is great for accommodating undergraduate students, third-year Ph.D. student in the Department of Integrative Biology Nathan Anderson has had a different experience as a UW employee and Ph.D. candidate.

“McBurney only covers my accommodations as far as they go into classes that I take,” Anderson said. “As far as accommodations within my capacity as an employee of the university — so accommodations in the actual lab space where I work — have all been coordinated with the department disability representative.”

Anderson started studying life sciences upon his acceptance into graduate school. As an undergraduate, he studied mathematics, which didn’t require any lab work.

Still, having research experience was important to Anderson as an undergrad, but he found it difficult to find a lab willing to accommodate his service animal.

“I do computational work because that’s really all that’s open to me,” Anderson said. “There’s a lot of options that are not open to me in the STEM field.”

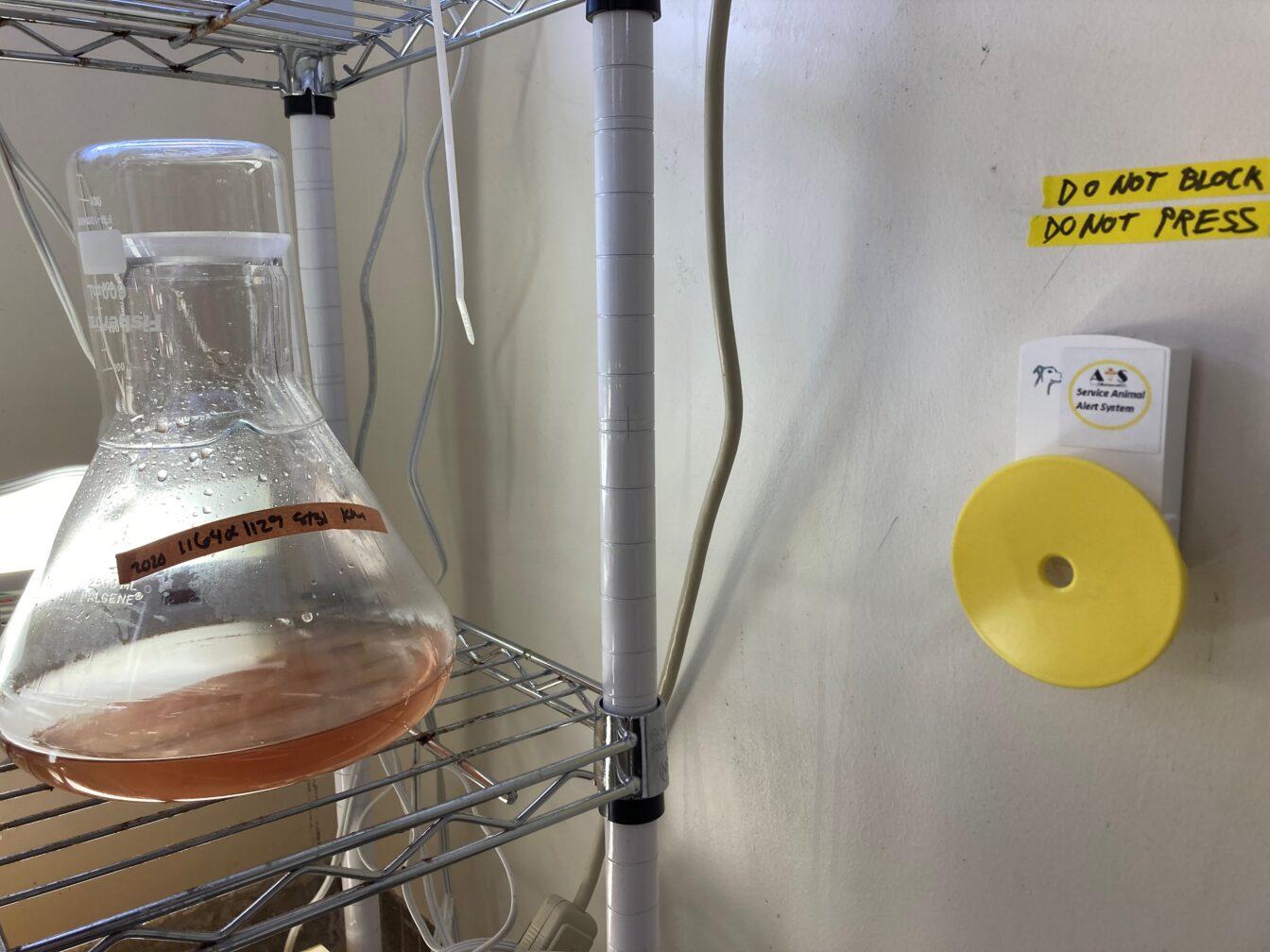

Though Anderson found a research job that addressed his needs, the same doesn’t go for everyone. He said people with certain disabilities cannot teach or participate in some microbiology and chemistry labs. Specifically, there are sterility issues and strict lab protocol when it comes to having a service animal.

Anderson and Sullivan believe representation of students with disabilities is so small in the STEM field because of exclusions. For other students with disabilities who would like to study STEM, getting a degree in their area of interest might not even be plausible.

What many fail to realize, however, is that much of this negative perception of being disabled in a STEM field comes from society failing to recognize the barriers it has erected surrounding the disabled community, according to Sullivan.

For example, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) sets standards and a clinical code of ethics universities that offer ASHA-accredited programs must adhere to. These Essential Functions can make it difficult for disabled students like Sullivan — who hopes to go into speech and language pathology — and other students with disabilities to pursue this career path professionally.

In an email to The Badger Herald, Sullivan said acceptance into affiliated programs can depend on an individual’s ability to perform, according to the functions outlined by individual institutions.

“It seems as though many individual programs have broadened their guidelines, but many programs still require students to have fine motor skills or be able to see, as well as exhibiting very vague verbiage surrounding physical abilities and demands in practicum settings,” Sullivan said.

Additionally, life science research for students with disabilities can be very “unwelcoming” and “competitive,” Anderson said.

If there were a larger number of people with disabilities in STEM, it would help curb negative perceptions associated with disabled people by making it common to see accessible features in society, Sullivan said.

“Engineering and how things are designed and made should really be centered around accessibility and the disability experience,” Sullivan said. “When you make something accessible, you’re not cutting non-disabled individuals off from using that.”

Societal changes like that would make a world of difference for anyone with a disability.

As for students like Anderson and Sullivan, being disabled in STEM brings much-needed transparency to issues that would otherwise go unnoticed.

“It helps me make an impact, I think, on people,” Anderson said. “I’m more verbal. It might help down the line.”