A partnership between the University of Wisconsin System and manufacturer Adapt Pharma will allow law enforcement and campus security across 10 campuses to have expanded access to naloxone — a medication that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose.

Officers on these campuses, including UW, will be provided with Narcan nasal spray at no extra cost. UW System President Ray Cross said this will be a critical resource for campuses across the system.

“The UW System has been actively working with recovery stakeholders in Wisconsin to demonstrate our shared commitment in the fight against opioid use, and this is an important tool for our officers,” Cross said in a statement.

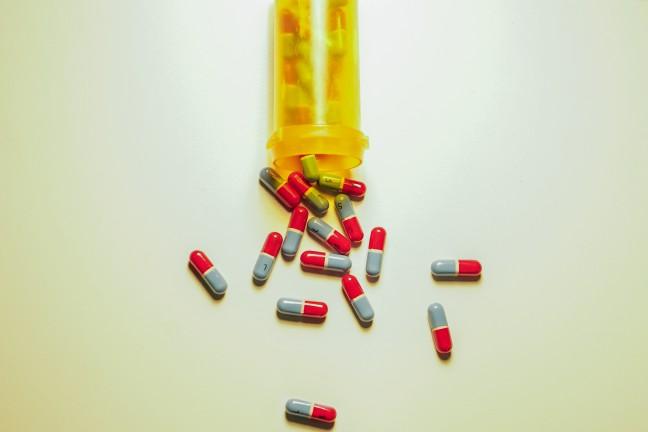

Naloxone blocks the effects of opioids on the body, Jenny Rabas, a substance abuse prevention specialist at University Health Services, said. It can be used in a nasal spray, needle or auto-injector.

Naloxone is also sold at Walgreens on East Campus Mall, Rabas said. She said it’s a good thing to have if you know of someone who is an opioid user or abuser.

“If you know of someone who is a user or abusing, it’s really important to get information about naloxone and always have in the back of your head that our first responders carry it,” Rabas said.

Live Free is a student wellness and recovery group on campus that provides a space for students who are in or are seeking recovery from substance use.

Co-chair of Live Free Stanley Kaymen said the initiative is a step in the right direction when it comes to addressing opioid use on campus.

“Obviously I hope that people are getting the help they need before it comes to the point they’re overdosing and need to be revived, but if it does get to that point, I’m fully in favor of making sure naloxone is there when people need it,” Kaymen said.

According to the 2016 Healthy Minds Study, less than 0.5 percent of UW students have reported a recent misuse of opioids, Rabas said. Around 7,000 students self-reported their experiences for the study.

While she is concerned about the opioid crisis, Rabas said the data shows little opioid abuse on the UW campus. There are other substances, like alcohol, that are more frequently abused, she said.

“We know from our data a small percentage of students report a misuse of opioids, however, we know it’s a crisis in the United States right now, so people might have family members who are affected or may know someone who’s using and want to have it on hand for that reason,” Rabas said.

While Kaymen agrees there are other substances more commonly abused, he said opioid abuse is definitely present on campus. It might be unclear to say how many students are abusing opioids because of how secretive the addiction is.

One of the issues Kaymen sees on campus is the disconnect between services offered on campus and students who need help taking advantage of those services.

“The help is out there, but they’re not really getting it,” Kaymen said.

A potential reason for this disconnect is the stigma surrounding seeking treatment for addiction, especially with the party culture surrounding UW, Kaymen said. An individual’s problem with alcohol or substance abuse might go unnoticed because it seems like everyone else is doing it, he added.

Even though a lot of the data shows most students are making low-risk choices, it’s easy to think most students make high-risk choices, Rabas said.

“We have lots of data to say people are making pretty low-risk choices,” Rabas said. “However, if you think everyone is making more high-risk choices, you’re more likely to use or more likely to normalize other people’s use.”

Rabas said it is also important not to demonize addiction but instead understand it is a sickness and empower those individuals in a positive way.

On the UW campus, Kaymen would like to see more people understanding the danger of substance abuse.

“I’d like to see a greater understanding of the dangers of substance use, especially certain substances and the roads it can lead you down,” Kaymen said. “[Also,] just a reduction of the shame and stigma around [substance abuse], so when people have these issues, they don’t feel like they have to hide it and they feel like it’s easy for them to ask for help.”