In April of 2012 the Mifflin Street Block Party loomed on the horizon, a dark harbinger of debauchery. Hoping to curb attendance that year, University of Wisconsin Dean of Students Lori Berquam took to YouTube with a video message for Madison students: Don’t go to Mifflin.

Despite her best intentions, Berquam’s video met a hard audience. Many students felt the video came off as patronizing and quickly flooded the YouTube page with negative ratings and derisive comments. A techno remix of Berquam’s video appeared within 24 hours of its publication. In short order, “Don’t go” became an internet punchline — a meme. Berquam described the video as “a disaster” on Twitter, and the University pulled it from YouTube hardly a day after its debut.

“At the time, it had it’s desired impact, although not everybody would want to admit that,” Berquam said.

Attendance at Mifflin 2012 did indeed shrink, dropping to around 5,000 in comparison to 2011’s estimated 15,000. For many students, though, the legacy of Berquam’s video overshadows its effects on the party.

Five years later, “Don’t go” remains a joke on campus, even though the students who witnessed its birth have since graduated.

“I don’t even think about the video now,” Berquam said, though she also noted, “I think my videos have gotten better.”

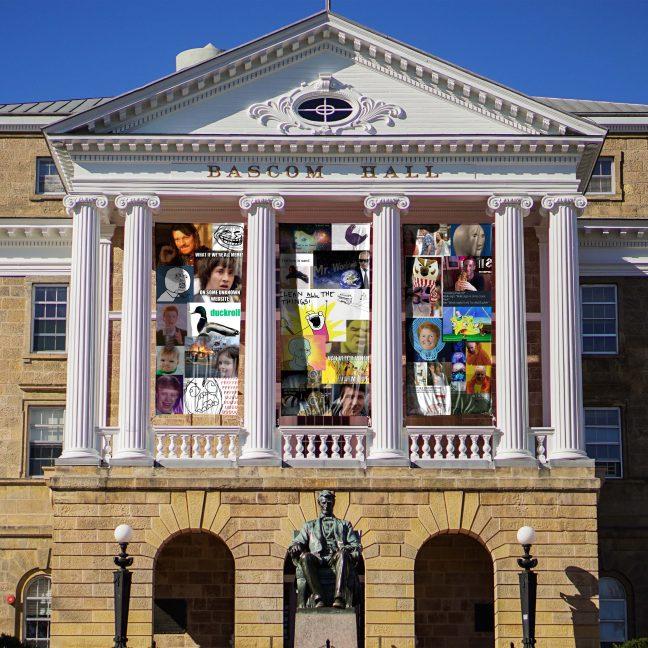

Still, “Don’t go” is part of an ever-growing collection of self-referential local humor — memes rooted in specific details of the student experience. These jokes often take the form of homemade image macros, contemporary memes adapted to suit the Madison community.

But these campus memes are more than menial laughs. They represent an online expansion of identity, a way of fostering community through the celebration of commonalities and shared experience. As memes migrate from esoteric corners of the Internet to corporate Twitter pages and mainstream politics, their role in our lives and our identities continues to evolve.

Rise of the meme

When Shane Linden started the Facebook page “UW-Meme County” in the fall of 2016, he had no idea he was starting a movement. Linden, now a senior, printed out flyers promoting the page and taped them on bathroom walls in the School of Human Ecology and Humanities. At the start, Linden’s page netted barely a hundred likes. But as word of the page spread, it gathered more and more users.

The page grew steadily, then the only active Facebook page dedicated specifically to UW-related memes. As page administrator, Linden would receive and post user submissions, though most of the content was his own.

“The first month or two I made a meme a day,” Linden said. “That was exhausting.”

Today, the page has some 3,800 likes. Along with the group UW-Madison Memes for Milk-Chugging Teens, also Linden’s creation, the UW meme community on Facebook numbers more than 7,000 members, though many may be duplicate members between the two forum’s networks.

The distinction between a Facebook page and a Facebook group is important: Whereas content on pages must be managed and published by designated administrators, groups are more democratic — once joined, all group members are free to post their own content.

Linden started the Milk-Chugging Teens group in the spring of 2016, hoping to democratize Madison memes.

“I didn’t want to be the person to decide whether or not something’s a meme,” Linden said. “This is just a much simpler and easier way for people to have their own memes out in the campus community.”

Users share memes frequently, submitting through the Meme County page as well as posting directly to the Milk-Chugging Teens group. Hot memes tend to net some 300 to 400 likes, while tepid submissions bring in 50. The content shared often uses familiar joke formats but modified in a campus-specific manner. Technically speaking, a meme is the structure for a joke — the Advice Dog upon which a user imposes text, or the act of sneaking someone a link to Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up.” However, in colloquial and more contemporary usage, individual images are often referred to as memes.

As the definition changes, so does the fodder for mockery. On campus, recent punchlines have been the widespread Wi-Fi outage or the Mentos viral ad campaign.

“That was just so good for the meme economy,” Linden said.

Other times, the focus of the memes are simply minor details of the student experience — the recorded crosswalk voice stating “walk sign is on to cross Park,” or lunch at QQ Express.

The joke isn’t so much the detail itself, but the meta-concept of finding humor in such banalities, Linden said. It’s about the shared delight of being in on the joke.

“Memes give people a culture to latch on to,” Linden said. “They express ideas that might otherwise just be stuck in individuals’ heads, and allow people to come together to recognize these, to come closer to the campus as a whole.”

Campus memes are by no means exclusive to UW. The University of California-Berkeley’s unofficial meme group, UC Berkeley Memes for Edgy Teens, was one of the first and now boasts over 100,000 followers. This summer, Harvard University rescinded admissions offers to 10 students connected to sharing offensive memes in a mass Facebook message between incoming students titled “Harvard memes for horny bourgeois teens.”

The meme group is becoming an unofficial tenet of the collegiate experience, and their rising prominence hasn’t escaped university officials, either. UW spokesperson Meredith McGlone said the university knows about UW’s Facebook meme scene.

“We’re aware of these pages, as well as many other UW-themed social sites, but do not actively monitor them or endorse their content,” McGlone said.

The meme and me

Facebook’s role as a popular platform for meme groups connects memes to real names, as opposed to sharing memes on anonymous forums. Because of this, memes take on greater meaning for our identity: what we share reflects our tastes, our knowledge, our interests.

For Robert Howard, director of UW’s digital studies program, memes and self-image are closely linked.

“People can actually use [memes] to express their personal identities, which are typically linked with places, like the institutions they work for or go to school at,” Howard said.

Junior Megan Bernards, a user on Milk-Chugging Teens, believes campus memes help bring her closer to the student community. They allow her to gain fellow students’ insights on what they think about different events, people or the campus itself.

Furthermore, the group also allows her to know that she is not the only one on campus who feels annoyed or bothered by something going on.

“Instead of getting frustrated or whatever, you just make jokes about it,” Bernards said.

Catalina Toma, associate professor of communication science, believes sharing these campus memes isn’t just about getting a laugh.

Meme pages and groups allow for an informal, accessible way to get a sense of belonging, to bring oneself closer with the local community — even if most of those users are relative strangers. This sense of community, Toma said, can contribute to better well-being.

“This is not about memes. It’s about identity, it’s about community, it’s about social connection. The memes are just a new tool that satisfies this,” Toma said. “There’s already a Badger community in existence, and these memes are capitalizing on that strong sense of identity by picking up on quirks that maybe only Badgers would understand.”

These meme pages can also help provide a connection to people who have moved beyond campus.

Will Meyers graduated last May, but continues to post in the UW meme pages. For Meyers, collegiate memes provide a remote, mobile way to still feel involved in the campus community.

“The memes allow you to reflect on your past Madison experience, those little inside jokes that only UW students would understand. It just makes you appreciate your time more.” Meyers wrote in a message to The Badger Herald. “They also keep you up to date on current events happening around the school. I’m told there is this guy who is like giving out mentos or something?”

Memes in modern discourse

Memes’ adaptability gives them appeal and makes them a potent vehicle for expression of any kind, personal or otherwise. Largely visual and adherent to familiar structures, memes are widely understandable. Professor Ron Howard said this accessibility, combined with the relatively low level of computer literacy needed to modify or spread memes, makes them well-suited for self-expression.

Beyond riffing on school rivalries or campus quirks, UW’s Facebook memes can also reflect current discussions in social justice and politics. As issues arise, so do memes in response. Posts appeared critiquing UU and Wando’s practice of censoring hip-hop from jukebox playlists, lambasting fraternities following conduct violations or criticizing the efficacy of the Associated Students of Madison.

It’s time UW and the Madison community widen its update of racism

“Memes are catering to this particular audience of college students who might find this visual medium and the humor much more appealing than a serious conversation,” Toma said.

And while they are no substitute for a serious conversation, memes can breach uncomfortable topics with the cushion of a familiar format and an informal tone, Howard said. They can comment on contemporary issues without belittling the problem itself and can spread that message to thousands.

Memes alone cannot bring change, but their digital mobility enables them to easily voice perspectives across platforms. For Linden, one of the most important elements of memes in advocacy is their lack of entry barrier.

“Unlike a lot of these satirical outlets, where you have to be part of an organization or newspaper, anyone can make a meme and deliver their commentary,” Linden said. “They offer a method of examining ideas, humor and concepts in a way that I don’t think we’ve ever really had in the past.”

And though their mobility can deliver important commentary and challenge institutions, the propagation of memes can just as easily spread toxic ideas, or normalize dangerous behavior. A notable example of this is Pepe, the notorious cartoon frog.

Originally the creation of cartoonist Matt Furie, the amphibian was appropriated as a symbol of White Supremacy and is now classified as a hate symbol by the Anti-Defamation League. Howard points out that the casual nature of memes can be dangerous, as it can implicitly normalize harmful behaviors or viewpoints expressed as a joke.

“It’s easy for us to dismiss these informal communications as, ‘oh well, he’s just joking.’ But the thing is that when we joke a lot over time, we’re both expressing our shared beliefs, and potentially changing them,” Howard said. “The danger there is that people begin to perceive [harmful behavior] as normal, as what we always do, and then it renders acceptable things that maybe as a society we shouldn’t think are acceptable.”

In the local meme scene, Linden says he hasn’t encountered any problems with the UW groups sharing hateful content. He speculated that Facebook’s lack of anonymity likely discourages these types of posts.

The future of the meme

While the meme seems eternal, the outlets through which they flow can be transitory. Facebook stands out as a significant outlet for meme propagation, joined by and perhaps surpassing outlets like Twitter, Reddit and 4chan. According to Toma, the meme’s shelf life seems promising, thanks to its close link to a sense of belonging. The platform across memes spread, however, isn’t nearly as secure.

“The impetus remains, and it will probably manifest itself in something new that we can’t even envision right now,” Toma said.

Though Linden’s Facebook meme monopoly continues to thrive, Linden places little stock in its longevity — but he doesn’t take it personally.

In a year he speculates his pages, despite their current popularity, could be dead.

“Someone’s gonna come up with a better platform, and people are gonna use it,” Linden said. ‘That’s just how the Internet works.”