After several years of planning, students at University of Wisconsin will have the opportunity to learn how to use forensic botany skills to solve criminal cases.

After a successful test-run during this spring semester, Botany 355: Forensic Botany, will continue to be offered as a course next spring semester.

The course is taught by professor Sara Hotchkiss, a UW botanist who works with botanical evidence to reconstruct ecosystems. Hotchkiss said she hopes the course will provide students with a real-world application of botanical science.

Looking at botanical forensics is a way to show how science can be applied in a legal context, Hotchkiss said. Science is all about evaluating evidence and using it to solve problems —which can really matter in legal cases.

Hotchkiss said botanical evidence is largely underutilized in court cases. The evidence can be used to establish the location of an event. For instance, specific pollens on a person can be used as evidence to prove that a person was in one place and not somewhere else.

“I hope that this class will encourage people to bring [botanical] evidence into decision making,” Hotchkiss said. “This country doesn’t utilize botanical evidence very much. The more lines of evidence we use, the better our decisions will be.”

Alex Wiedenhoeft, a research botanist and team leader for the U.S. Department of Agriculture forest service, is the adjunct assistant professor for the course. As a volunteer for the class, Wiedenhoeft teaches during his own free time.

Wiedenhoeft has used botanical identification within his own career to help in various civil and criminal cases. He has traveled across various parts of the world teaching courses to law enforcement officers about wood identification and how it can be used as evidence. He has also worked with museums, using wood identification to study the wood cultures of indigenous groups.

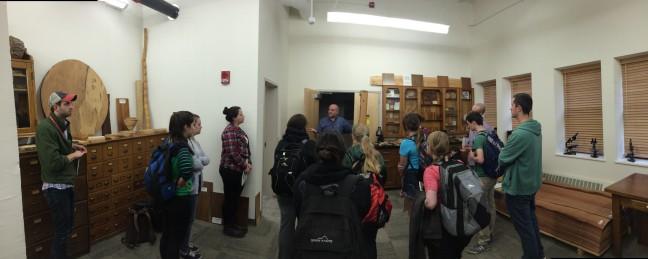

The course has taken advantage of several hands-on opportunities, including a mock stomach contents lab. At the end of the course, Wiedenhoeft said students will go to a mock wood science lab where they will have to analyze fake evidence and work in pairs to develop forensic reports.

“This course shows how scientific material can be used in the real world and solve problems for real people,” Wiedenhoeft said. “We are bridging the gap between textbook and real life.”

Each team will then have to present their evidence and argue for or against their case, and will be cross-examined by another team from the class. It is through opportunities such as this — that try to draw on real life — that students are able to learn what botanical forensics is all about, Wiedenhoeft said.

The course continues to look for more opportunities on and around campus for the class to get hands-on, real world experience, Wiedenhoeft said.

“There is ample science to back up the forensic application of botany, but there seems to be a lack of awareness of how powerful and ubiquitous it can be. We want to take students who are excited, passionate about botany, and show them what is out there,” Wiedenhoeft said in UW statement.

Hotchkiss said she would like to see the government expand the forms of evidence they use in lawsuits. She said she believes botanical evidence is one place law enforcement could start.

But more importantly, Hotchkiss said the course will teach students the scientific reasoning behind botanical evidence, and how they can use it to problem solve.

“Forensics is a great way to teach how science works,” Hotchkiss said in the statement. “It’s problem solving. This is changing, but too many introductory classes are about what I call ‘stuff scientists have learned.’ The forensic approach is about how scientific reasoning works. The fun of being a scientist is figuring out how stuff works and solving problems and mysteries.”