A phase 2b clinical trial spearheaded by a University of Wisconsin professor, a UW alum and other researchers from across the country found an optimal time for intense motor therapy after a stroke.

The School of Education’s Associate Dean Dorothy Farrar Edwards and UW alum Shashwati Geed were a part of the team that led the study, which is innovative because heightened motor recovery in a time-limited window has not been well-documented in humans despite equivalent studies demonstrated in animal models.

The clinical trial answered an important question about the best timing of intensive motor therapy for people who have experienced strokes, Farrar Edwards said.

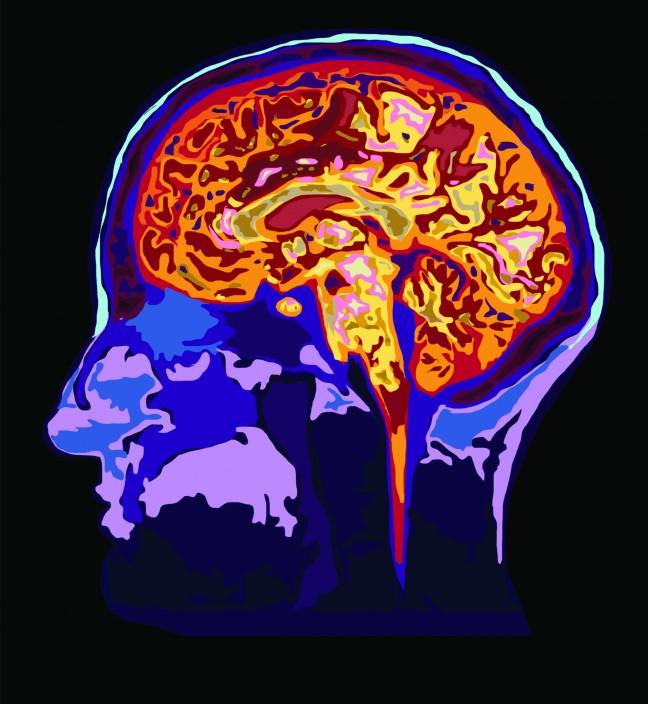

Geed said this discovery is “exciting scientifically” because it means neural circuits are particularly receptive to being shaped by the environment and by therapy.

“Few stroke rehabilitation trials so far had shown significant, meaningful recovery beyond what is shown by spontaneous recovery and standard rehabilitation,” Geed said.

The CDC estimates over 795,000 people in the U.S. suffer from strokes every year. Strokes are the leading cause of serious, long-term disability.

The findings of the clinical trial determined a sensitive or optimal period of therapeutic intervention of 60 to 90 days after a stroke with lesser effects before 30 days and no effect six months or later after a stroke. Geed said this does not mean individuals do not recover at later time points if given therapy.

“There is a sensitive period when the brain circuits are more receptive to therapy for a brief time,” Geed said. “We need to make the most of this time and get patients the appropriate therapy during this window to heighten recovery.”

In the study, twenty hours of self-selected intensive motor training were added on top of the trial participant’s standard rehabilitation. Stroke patients were randomized with outcomes compared to the control group that only received standard motor rehabilitation.

Farrar Edwards led the design of rehabilitation activities to encourage internal motivation of stroke patients by finding activities they enjoyed and found meaningful.

“My part of the study was to figure out how to motivate the people enrolled in the study to work really hard even though it was very difficult and challenging,” Farrar Edwards said.

Participants were allowed to choose what they wanted to do without compromising the fidelity of the study, which is not normally done in stroke treatment trials, Farrar Edwards said.

The next step is to test the results in a larger group as part of a phase 3 clinical trial and determine optimum dose of therapy to achieve the best effects during this time-sensitive window.

More information about the study and its findings is available through Georgetown University’s website.

The release of this study’s publication is dedicated to the principal investigator, Alexander W. Dromerick, who died before its release.