A pharmacy professor gave a talk for Wednesday Nite @ The Lab called “Fighting Antibiotic Resistance with Broken Scissors.”

Associate professor for the School of Pharmacy Jason Peters highlighted the importance of bacteria in the human biome, food fermentation, infections, biofuels and research tools.

“Humans are covered in bacteria — they contain millions and billions of bacteria, and these bacteria are key contributors to human health,” Peters said. “In some cases, they actually improve the functioning of our microbiome. When things don’t go right, these bacteria can actually work against us.”

Bacteria can be used to convert plant material into biofuels, particularly jet fuels. Commercially, bacteria are used in the large-scale production of yogurt — they give yogurt its unique texture and flavor.

Peters said bacteria interact with viruses, which try to infect them.

“Bacteria are constantly under attack by new viruses called phages,” Peters said. “There are about five to 10 phages for every bacterial cell in the world, and there are 1,023 phage infections per second.”

Peters said the overwhelming ratio of phages to bacteria makes it hard for bacteria to defend themselves. Therefore, they must develop weapons and new “generalized” and “adaptive” ways to fight not one, but many kinds of phages. Yogurt manufacturing companies must combat phages who can easily wipe out a complete bacteria population from a culture.

North Carolina State University microbiologist Rodolphe Barrangou observed when phages are added to a culture containing bacteria, most of the bacterial population dies. But a select few bacteria develop resistance to the phages and survive.

“What the really interesting thing that he found is that the resistant bacteria had actually incorporated pieces of the phage into their genome,” Peters said. “Somehow, the bacterium looked at the phage that was infecting it, grabbed its DNA sequence, inserted it into its genome, and now was resistant to the phage. That’s what CRISPR is doing. CRISPR is allowing bacteria to become immune to the phages.”

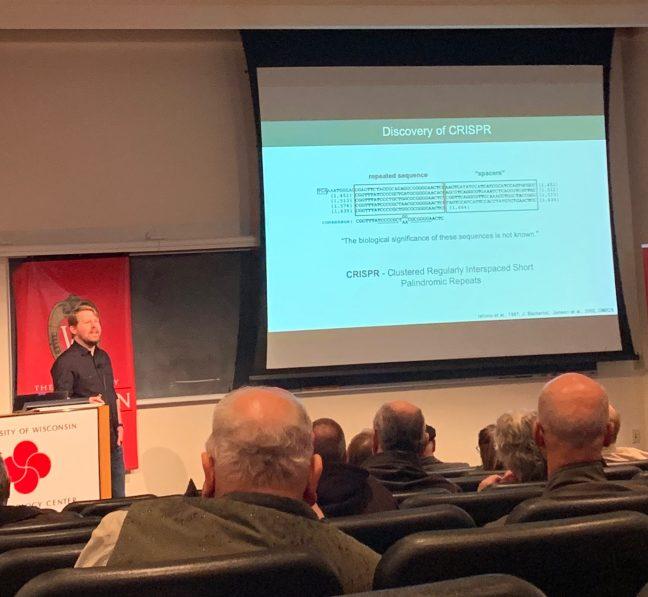

CRISPR, which was discovered in Japan during the 1980s during the sequencing of a gene, is a process of editing a gene, Peters said.

Like they can develop a resistance to phages, bacteria can develop adaptive mechanisms and become resistant to antibiotics. CRISPR editing can replace antibiotics to solve the global problem of how bacteria are becoming resistant to antibiotics at an alarmingly exponential rate, Peters said.