Gathered at the top of the Capitol steps Saturday, a crowd shouted “Recovery is possible!”

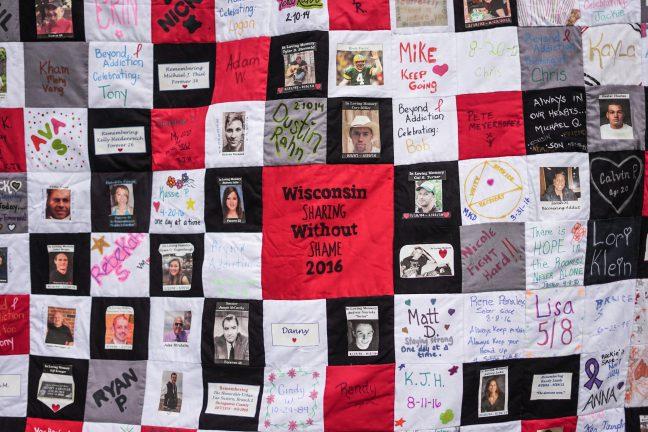

Joined hand in hand, recovering addicts, families and friends of loved ones lost to opioid and heroin addictions stood together and spoke for those who struggled with the disease.

Though the atmosphere of the crowd remained positive, the struggle of addiction in Wisconsin loomed as a reminder of why members of the community gathered at Rally for Recovery for the third year in a row.

While the use and abuse of heroin and other opioids continue to rise across the nation and the state of Wisconsin, recent movements toward addressing the state’s addiction epidemic aim to increase education and fight stereotypes.

Rep. John Nygren, R-Marinette, author of the Heroin, Opioid, Prevention and Education Agenda, joined participants and stressed the need to combat the state’s heroin and opioid epidemic.

In an effort to educate Wisconsin citizens about the state’s worsening addiction problem, Nygren highlighted the importance of removing barriers that prohibit people from helping those who suffer from heroin and prescription drug overdoses in a timely manner.

One barrier is the lack of access to naloxone, commonly known as Narcan, a drug that can save someone’s life following an opioid overdose.

Naloxone reverses an overdose by blocking opioid receptors in the brain and temporarily countering the effects of the overdose.

In August, Gov. Scott Walker expanded access to naloxone and allowed pharmacists to dispense the drug without prescriptions. They’re now commonly available at most drug stores, including Walgreens and Walmart. Now, community efforts have focused on educating the public on how to administer naloxone affectively.

Raising community awareness

According to data from the Madison and Dane County Department of Public Health, almost 7,000 people went to the hospital due to poisoning between 2006-07. Sixty-seven percent of the poisonings were due to prescription, over-the-counter and illicit drug overdoses.

With the increasing rate of opioid-related overdoses and deaths, Rally for Recovery isn’t the only way organizations like Safe Communities of Madison-Dane County and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services work to raise awareness about Wisconsin’s opioid problem.

Heidi Olsen-Streed, AIDS Resource Center of Wisconsin prevention specialist, is part of an initiative to raise awareness and educate the public about opioid drug abuse and addiction.

With a syringe in one hand and a filmy green liquid in the other, Olsen-Streed travels around Wisconsin to train members of the community how to administer naloxone and reverse the effects of an overdose in a matter of seconds.

During an Aug. 31 training session at Madison Public Library, Olsen-Streed addressed 20 members of the community who were friends and family of addicts or had lost someone they love to an opioid overdose.

The Safe Communities training is part of a partnership with the city of Madison and Dane County to emphasize prevention and intervention, according to a Safe Communities statement.

Safe Communities held several naloxone trainings over the summer and plans to host another in November.

Olsen-Streed said administering naloxone effectively could mean the difference between life and death.

“This is a time-sensitive intervention … unfortunately, if a person has no pulse, Narcan won’t reverse the effects of that,” Olsen-Streed said.

Responding to overdoses

In 2011, naloxone was administered 270 times following emergency service calls, according to Safer Communities of Madison-Dane County.

Last year, the Madison Police Department trained and equipped 450 officers with naloxone to meet the demand of the growing number of service calls for overdoses.

Aleksandra Zgierska, assistant professor in the School of Medicine and Public Health, said the ability to equip officers and other emergency first responders with naloxone is a result of legislation passed in April.

The changes have allowed first responders, police officers and members of the community to access and administer naloxone without a written prescription. This expands the potential for people to save those who struggle with addiction, Zgierska said.

“[Police officers] are thrilled to [have the ability] to save a person’s life,” Zgierska said. “They can make a difference right at that moment, at that time.”

But even with the availability of prescription-free naloxone, the problem of addiction remains.

Joel DeSpain, MPD spokesperson, said police reports make it clear there are many people who want help with their addictions, but the strength of their addiction overcomes their ability to seek help.

“We determined several years ago this opioid addiction is not something we are going to be able to police our way out of,” DeSpain said. “Naloxone is going to save lives, but we need to get at the addiction.”

Price to pay

Though the 2015 law enables those with non-prescribing privileges to dispense naloxone, higher costs could still inhibit people’s ability to purchase the drug.

States around the country are working to make naloxone more readily available and Wisconsin has been a leader in that movement, Nygren said.

Nygren said the price of the nasal form of naloxone has become more costly while other forms of naloxone remain relatively affordable. Nygren has been working with insurance companies to lower the cost of the nasal spray.

According to GoodRx, two doses of Narcan nasal sprays cost $136.90 while two syringes of naloxone cost $35.94 at Walgreens.

“When it’s a life-saving drug, we can’t get to a point when it’s cost prohibited,” Nygren said.

But the price of naloxone is not entirely within the state’s power to control, since prices are federally regulated. Relatively few companies make naloxone, so there are few sources where it’s available, Nygren said. Additionally, the growing demand for naloxone has increased the cost, he said.

A 2015 grant from Kaleo Pharmaceuticals provided MPD 600 doses of naloxone to equip its officers.

“Right now, from a state perspective, making sure [naloxone is] still in the first responder’s hand so that when there is an overdose you can save a life, that’s my number one priority,” Nygren said.

Destigmatizing the disease

Naloxone gives addicts a second chance to live when their addiction almost takes their life away, Zgierska said. It gives addicts the chance to change for the better.

Though the life-saving drug can offer an addict the opportunity to receive help for their disease, naloxone is still surrounded by the stigma of addiction because some believe opioid abuse is based on character, Zgierska said.

To understand the necessity of naloxone, people need to move past the belief that overdoses only happen to people who are characteristically flawed, Zgierska said.

Zgierska said opioid overdoses can even happen to people who are properly taking their medications as prescribed.

Doctors who treat patients with opioids often recommend a prescription of naloxone in case the patient accidentally overdoses on their prescription, Zgierska said.

People have to be kept alive if they are going to be helped with their addictions, Zgierska said. Naloxone cannot replace treatments for addicts, but it is part of a comprehensive approach to give those who overdosed a chance to change.

To combat the stigma and to help people understand the importance of naloxone, more people need to be educated about overdosing intervention and prevention, Zgierska said.

“Unfortunately, there are not many people who are educated about [opioid abuse and addiction],” Zgierska said. “That’s exactly what we should be doing — promoting better education.”