The University of Wisconsin researcher who’s worked to develop a vaccine for Ebola said Monday that the vaccine has shown promising results and could even enter the clinical trial phrase in two years.

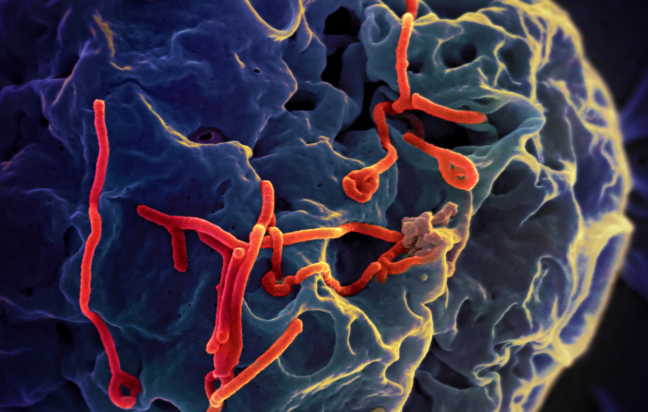

Professor Yoshihiro Kawaoka’s vaccine is comprised of a strain of the Ebola virus called Ebola VP30. The strain lacks the gene that allows the virus to replicate in normal cells so the virus cannot grow.

To prove the vaccine’s efficacy, Kawaoka said he and his team tested it on various animals. After experiments showed the effectiveness of the vaccine in rats and guinea pigs, Kawaoka’s team advanced testing the vaccine on non-human primates.

“Primates are the golden standard for Ebola work, but for ethical reasons we have to show the efficacy of the vaccine in rodents first,” Kawaoka said.

The control group Kawaoka’s team immunized with a deactivated version of the Ebola virus was not protected and subsequently died, he said.

When the research team immunized another group of animals with the vaccine once, one animal fell ill, but recovered and survived. No animals became ill in the group immunized with the vaccine twice.

Even though the virus can grow in specially modified cells, Kawaoka downplayed safety concerns due to exposure. Kawaoka said the team managed to kill the virus with hydrogen peroxide without diminishing its effectiveness.

The virus is stored in Montana because Wisconsin’s facilities do not have an adequate biological safety level, Kawaoka said.

Kawaoka said he and his colleagues are now searching for an adjuvant, a substance that will require the vaccine to be administered only once, not twice. Once they have found a suitable adjuvant, he said they will be closer to having clinical trials with humans.

Kawaoka traveled to Sierra Leone to “develop research collaborations” and infrastructure to detect, study and deter the Ebola virus.

While working with the vaccine, Kawaoka and his team have been collecting blood samples from Ebola patients who have died and patients who recovered. Then they compared them by testing their responses and studying the differences between the two.

“By understanding the difference in host responses between patients who recovered and those who died, we may be able to change host responses back to normal and save people,” Kawaoka.