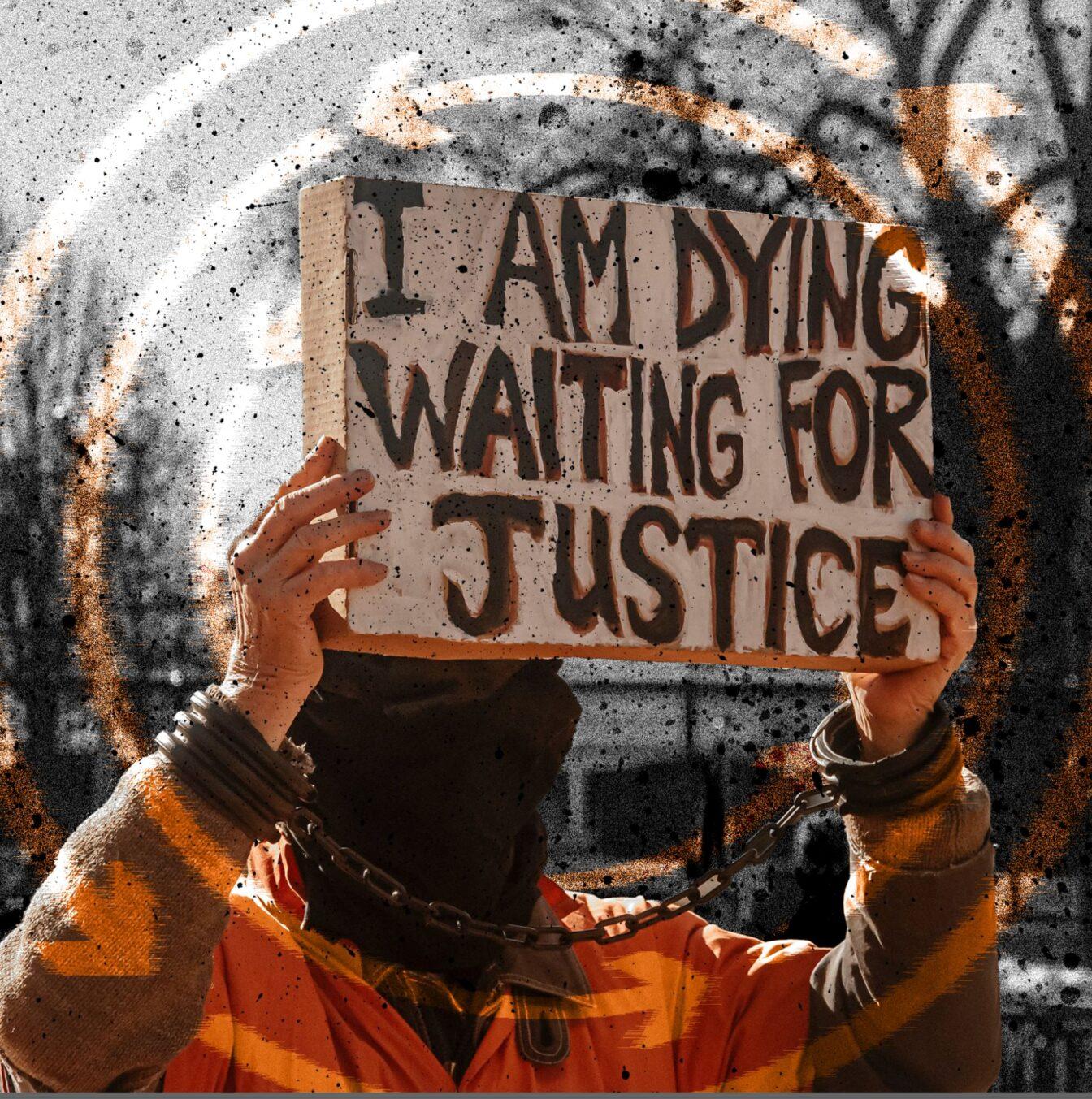

Milwaukee native Ramiah Whiteside was just 17 years old when a judge sentenced him to 47 years in prison.

While Whiteside only served 20 years of his sentence, he cycled through 11 different correctional institutions, bouncing between super maximum security facilities all the way down to community custody. In consistently overcrowded prisons – where three people would sometimes be packed into a cell designed for one person – with little respect for individual privacy, prison was a dehumanizing experience for Whiteside.

But Whiteside’s punishment didn’t end when his sentence was over. His criminal conviction made it difficult for Whiteside to find stable employment and move up in the workforce. Whiteside said he witnessed how the constant anxiety and stress that individuals endure during their sentence can create barriers to trusting their closest friends and family after their release.

Whiteside’s story is his own, but he is just one of thousands who have spent years inside Wisconsin’s correctional facilities with similar post-incarceration struggles. Many of these individuals are people of color from segregated urban areas – communities that are disproportionately impacted by mass incarceration in the state.

As the inequitable realities of prison and difficulties of re-entry continue to prevail in Wisconsin correctional facilities, criminal justice experts, formerly incarcerated individuals and policymakers work to make Wisconsin’s carceral process more rehabilitative and productive, attempting the daunting task of breaking long-perpetuated cycles that plague the criminal justice system.

The importance of a ZIP code

Whiteside’s home city of Milwaukee, one of the most segregated cities in the country, exemplifies the deep-rooted issues within Wisconsin’s criminal legal system. Milwaukee residents living in the poorest neighborhoods face disproportionately high rates of incarceration, with decades of ineffective policy choices leading to these disparities.

High rates of imprisonment can devastate neighborhoods as younger generations are left without role models and community leaders. For example, a study by University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee found that 24.1% of Black males in the 53206 zip code between the ages of 20-64 were in the carceral system in 2013.

“If you just take one zip code, which is the 53206 zip code, it’s basically a ghost town as far as males between the ages of 14 and 40,” Whiteside said. “There are missing pieces because a majority of that demographic is incarcerated.”

The 53206 zip code is not the only area hit hard by incarceration on the basis of race in Wisconsin. The problem is pervasive throughout the state, especially for marginalized communities as 1 out of every 36 Black men in Wisconsin was in prison in 2021 – the highest level of disparity in any state.

The disparities within Wisconsin’s prison system did not emerge incidentally. By a wide margin, the U.S. incarcerates more people than any other country. This gap can be largely attributed to the War on Drugs, which led to the adoption of mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses in the 1980s and 90s. As a result, the prison population in 2015 was ten times higher than in 1980. Ashley Nellis, a senior researcher at the Sentencing Project, said the federal War on Drugs led to the original expansion of the prison system.

These policies perpetuate systemic racism as people of color suffer from rampant discrimination in the criminal legal system, from the way they’re policed to the sentences they receive. Despite comprising only 13% of the U.S. population and using drugs at a similar rate to other racial groups, Black people make up 40% of people incarcerated for drug charges.

Wisconsin lawmakers expanded on the policies of the War on Drugs by adopting truth-in-sentencing laws which make it harder and in some cases impossible for prisoners to get released early on parole – an essential process for people to transition out of incarceration.

Originally, politicians advocating for truth-in-sentencing claimed that removing opportunities for parole would incentivize judges to give shorter sentences, but punishments only became harsher after truth-in-sentencing policies were enacted. Christopher Lau, a lawyer and current director of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, said incarceration rates drastically increased after Wisconsin adopted these policies.

“So if you compare us to a state like Minnesota which has similar demographics and similar crime rates, we incarcerate twice as many people,” Lau said. “We end up paying to incarcerate all those folks even though there’s no data that shows it makes us any safer.”

When Whiteside went to prison in 1995, the prison population was exploding as former Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson led the biggest expansion of the carceral system in Wisconsin’s history. The state’s prison population rose 677% between 1978 and 2018, but prisons’ operating capacities didn’t increase at the same rate. As of 2021, Wisconsin prisons are 6,000 inmates over capacity.

Former Republican Gov. Scott Walker attempted to resolve Wisconsin’s capacity issues by sending inmates to private prisons in other states. Walker wanted to make Wisconsin tougher on crime as an early supporter of truth-in-sentencing policies and proponent of bills to lengthen criminal penalties.

“The real sort of loyalty to this mass incarceration enterprise is this misguided notion that you can punish your way out of crime,” Nellis said. “We’ve had crime declines and some of them can be attributed to more incarceration, but we could’ve achieved these low rates of crime that we have relative to the early 90s without damaging so many lives and communities.”

In recent years, some Wisconsin politicians have acknowledged the shortcomings of their policies. Though Walker pushed for higher incarceration rates early in his career, he rarely touts it as one of his policy accomplishments.

Similarly, Thompson expressed regret about his role in the expansion of the prison system. During his tenure as the UW System President that ended in March, Thompson said he hoped to shift the goals of the carceral system.

“I built too many prisons,” Thompson said to the State Journal. “I think we need to be much more interested in rehabilitation.”

Collateral Consequences

Collateral consequences are the legal disabilities imposed on criminals which greatly impacts prisoners’ lives.

“Having a record is very challenging,” Nellis said. “That’s the big issue with a felony conviction. It’s something they call a collateral consequence – they can’t move forward when they try to do something that’s right, like buy a home.”

Criminal background checks can make finding a job difficult, taking away some opportunities for prisoners to support themselves and their families. Some state governments go a step further to restrict access to public housing and other forms of needed public assistance based on criminal background checks.

In the face of these harsh post-incarceration realities, criminal justice experts emphasize the fact that convicted criminals are not able to electorally push for change without the ability to vote. People of color, specifically Black people, are disproportionately affected by disenfranchisement due to a previous conviction – an estimated 8% of voting-age Black people are denied their right to vote because of criminal records.

But even if all legal barriers were removed, prisoners’ experiences and backgrounds still makes it challenging for them to move on with their lives. Because prison sentences don’t address the root causes of crime, prison alone can leave people struggling with heightened poverty and exacerbated mental illness after their sentence, Whiteside said.

With drug problems and mental illness left untreated, prisoners struggle to transition back into normal life. A study analyzing the social determinants of health found prisoners are 129 times more likely to die of a drug overdose within two weeks after their release.

“If you have trauma, substance abuse or mental illness that’s present before incarceration … upon release, all of the same factors are still present,” Whiteside said.

It seems intuitive to believe that the more criminals that are incarcerated, the less crime occurs, but Todd Clear, a criminologist and professor at Rutgers University-Newark, reached a different conclusion. After doing years of research, Clear found that imprisoning large portions of a community does not decrease crime rates. Instead, mass incarceration creates intergenerational issues that can actually perpetuate criminal activity.

“On a block, for example, you can have as many as five people going to prison every year. So, you can really make prison part of the ecological reality of that block,” Clear said.

On an economic level, imprisonment makes it harder for people to provide for themselves and their families as going to prison reduces average lifetime earnings by 40%, Clear said.

“In a neighborhood where most adult males have been to prison, those adult males simply cannot generate the type of economic activity that neighborhoods need to thrive,” Clear said. “What you’ve done is concentrated intergenerational family breakup and poverty through the mechanism of the prison system.”

In highly segregated areas like Milwaukee, poverty is concentrated in Black and Hispanic communities, and mass incarceration directly contributes to this disparity. Concentrated poverty and a lack of social control makes people more likely to commit crime, and more crime leads to more imprisonment, Clear said. This vicious cycle creates areas with excessive incarceration rates that experience higher crime levels.

Even people who don’t commit crimes face challenges and harsh consequences resulting from Wisconsin’s criminal justice system set-up. Lau said Wisconsin has a particularly poor system for compensating wrongfully convicted people. People who qualify for compensation in Wisconsin must prove their own innocence, and the maximum state compensation someone can receive is $25,000. By comparison, Lau said a wrongfully convicted person can receive up to $1 million in Texas.

“When folks are wrongfully convicted and released, in a lot of states there are policies to compensate folks for the time they’ve been incarcerated,” Lau said. “Among the 35 or so states that have this policy, Wisconsin probably has the worst bill.”

Recidivism, rehabilitation and reentry

Recidivism is the tendency of a convicted criminal to relapse into criminal behavior after incarceration. While Wisconsin’s recidivism rate is close to the average for all states in the U.S., over a quarter of all prisoners in Wisconsin are convicted and sentenced again within two years of their release from prison.

In his experience, Whiteside said recidivism occurs because prisoners lack opportunities for self-improvement while incarcerated. Criminals don’t return to prison because they want to, but because they are released into the exact conditions that got them into crime in the first place, he explained.

“It’s just about the same setup as when you left. More likely than not, you’re going to be exposed to the same issues that lead to poor choices,” Whiteside said.

Reacclimating to the workforce can be complicated without vocational and educational opportunities. For example, the proliferation of computers happened while Whiteside was locked up, and he had to catch up with 20 years of technological advancement. Whiteside said was lucky to have friends and mentors during this transition, but he said not everyone has these connections.

If all prisoners had access to education and rehabilitation, their lives after prison could be different.

Michael Endres said he is a perfect example of the importance of these programs.

Originally from Madison, Endres was incarcerated as a teen and served eight and a half years of a 17 year sentence. Endres had access to credit-bearing college courses in prison which he said was the number one reason he found success after incarceration. These courses gave him the ability to enroll at UW-Whitewater.

Now, Endres is a faculty lecturer at University of Hawaii-Manoa with a PhD in clinical psychology from the University of Indiana.

Endres said he was very impulsive as a young man, and his lack of self-control ultimately wound him up in the prison system. But Endres found opportunities to change these behavioral tendencies through cognitive treatment programs in prison.

“I use[d] a lot of the skills I was taught in those cognitive programs while I was incarcerated to help control myself when I got out and make better decisions,” Endres said.

Today, Endres is the project director and architect of the Honolulu Offender Reentry Program. The Reentry Program gives people access to educational and rehabilitative opportunities as they transition out of prison.

The Honolulu Offender Reentry Program provides these individuals with sober living, employment and educational resources and a network of peer mentors. The Honolulu Offender Reentry Program only accepts moderate to high risk individuals for its services, a group that on average has a 60 to 85% recidivism rate within three years.

The result of the program is a recidivism rate of less than 25%, according to Endres.

“I’ve built some of those things [educational and rehabilitative opportunities] into our reentry program because those things were critical for me, and a lot of people don’t have those things,” Endres said.

While Endres’s program helps people after their release, some organizations in Wisconsin seek to help prisoners during their sentence. The Odyssey Beyond Bars program, which started in 2019, offers credit-bearing UW courses to people in Wisconsin prisons. Former prisoners can then enroll in technical schools or UW campuses around the state. According to OBB’s website, the program has reduced its students’ poverty rate from 87% to 45%.

The effects of Odyssey Beyond Bars’ program have also been passed down to the next generation, with two thirds of OBB participants believing their experience with the program spurred their children’s interest in college.

The cost of educational programs pales in comparison to the cost of recidivism – every dollar spent on correctional education saves about four to five dollars of incarceration costs.

Change is taking place at the state government level as well as Wisconsin’s Department of Corrections has taken steps towards improving correctional education. John Beard, the director of communications at the DOC, said the agency has enacted various programs to provide education and reentry services to inmates in an email to the Badger Herald.

The 2nd Chance Pell Program, a collaboration between the DOC and Madison Area Technical College, has given prisoners the opportunity to take classes at MATC. The DOC works with the Odyssey Beyond Bars program to offer additional classes from UW-Green Bay and UW-Parkside. The agency has also utilized $500,000 to secure vocational equipment for prisoners, Beard said.

But the DOC can only do so much without better criminal justice legislation. The process to implement legislative action is slow moving though — Governor Tony Evers’ proposed several criminal justice reforms in his 2021-23 state budget, but the state legislature did not approve any of them despite previously claiming support for some measures.

‘Shifting the Paradigm’

Better education and rehabilitation programs may be necessary to improve Wisconsin’s prison system, but some experts think that’s not enough.

Endres believes that change can’t come from government institutions alone, but businesses also have to take responsibility for the communities they operate in. If companies look past criminal records, they can give former inmates opportunities to rise up in the ranks, enabling individuals with convictions to provide for themselves and their families, Endres said.

Clear proposed a more direct solution to problems resulting from mass incarceration — incarcerating less people.

“Almost every kind of reentry strategy that has been studied has been found to work in some places well and not work in others but never eliminates recidivism,” Clear said.

If properly implemented, Clear said policies to reduce prison sentences wouldn’t create the crime spike that some criminologists anticipate. Providing support for this argument, prisoners throughout the country were released – including some in Dane County – to reduce inmate populations when the COVID-19 pandemic struck.

Even though prison populations dropped by a third during the pandemic, Clear said crime rates were virtually unaffected by these early releases. According to the Wisconsin State Journal, the number of overall arrests decreased, less people got stuck in jail due to the inability to pay bail, and fewer individuals were incarcerated for parole or probation violations with the loosened policies in Wisconsin.

But this progress is fleeting. COVID-era changes to the criminal justice system were not envisioned as long-term, true reform goals, which officials in Dane County have already acknowledged, contending some COVID adjustments were not sustainable. The reduction in the prison population ended with the pandemic’s recession as state incarceration rates shot back up in October 2021.

Regardless of the rehabilitative services prisoners receive to help with reentry or reforms to incarcerated less people, the main focus, Clear said, should be preventing the root causes of crime – not trying to repair a system that’s broken.

“We’ve been trying to make prisons rehabilitative for literally centuries, and for centuries we’ve been failing,” Clear said. “We walk around with this idea that an institution, like a prison, can be turned into a place where people are changed for the better.”

Whiteside has transformed his life since he left prison in 2019. Like Endres, Whiteside now works to help people stuck in Wisconsin’s prison system. He currently works for EXPO, a Wisconsin based organization of formerly incarcerated people that seeks to reform the state’s penal system.

Whiteside said people have to look past the desire to be ‘tough on crime’ to support people suffering from poverty, mental illness and drug abuse instead of punishing them. Ultimately, he said they have to understand that the current system of mass incarceration can be changed for the better.

“If people are more educated about what the expectations can and should be for corrections, and community engagement, then we can start shifting that paradigm,” Whiteside said.