In 1960s Afghanistan, women walked through vibrant, fruit-filled marketplaces without dress restrictions. Modern finance and newspaper buildings were constructed alongside traditional mosques and mud-brick houses. All children were educated through the high school level, and some women went to college to become doctors.

Sixty years later, the Afghanistan of the ‘60s is a fading memory. Since the Soviet Union’s 10-year occupation until 1989 to promote a communist government, Taliban control in the 1990s ushered in harsh restrictions on the rights of women and religious minorities, including widespread public executions. The U.S. invasion of the country in 2001 returned many freedoms for women but also caused infrastructure destruction and civilian deaths.

The U.S. decision to remove all troops from Afghanistan by the 20th anniversary of 9/11 in many ways brought the country back to its same state before the U.S. presence. In August 2021, Islamic State terrorists suicide-bombed U.S. evacuation efforts out of Kabul, killing 60 Afghans and 13 American soldiers. The U.S. returned the attacks with a drone strike they claimed to be directed at an ISIS car bomb, killing 10 Afghan civilians, including seven children.

Planes carrying Afghan refugees rapidly departed the Kabul Airport, leaving refugees clinging to the undercarriage of the plane to fall to their death upon takeoff. Others were trampled trying to enter the airport gates. An Afghan baby boy was hurled over barbed wire into the arms of a soldier and remains separated from his immediate family, who successfully evacuated to the U.S.

The Taliban celebrated their rapid takeover of Afghanistan, vowing to return order to its citizens using strict Sharia law. Now, women face losing their rights — from leaving their homes to receiving an education — while men confront the threat of being killed for their ties to the U.S. military or evacuation efforts.

The Taliban resurgence has ripple effects on the massive Afghan refugee population around the world, including Wisconsin where nearly 13,000 Afghan refugees settled at the Fort McCoy military base only to face a laborious legal journey to resettle in nearby cities.

For those refugees and their families, the traumatic scenes at the Kabul Airport and the reality of a Taliban-controlled Afghanistan do not stop at the airport gates — they haunt Afghans scattered across the world who long for the cultural, intellectual and artistic complexity hidden behind the country’s battle scars.

Escape to Fort McCoy

Rahim Safi, a graduate structural engineering student, was taking his final exams when the Taliban invaded Kabul. Though he managed to leave the country on one of the last American flights out of Kabul along with many other refugees now at Fort McCoy, he said getting into the airport was a struggle.

“Leaving my country was one of the toughest things I have done in my whole life,” Safi said. “The first part was how to get in contact with the U.S. side of the [Kabul] airport and the other part was how to cross the Taliban checkpoints and the crowd and chaos at the gate.”

Safi grew up in a northern province in Afghanistan and then moved to Kabul so his sister could get a good education. When the Taliban took Kabul, he was stuck in the city for 10 days before escaping with his sister to the airport.

The exodus took a physical and emotional toll. Safi and his friends, who studied in Afghanistan for years, hoped to work in the country after graduating from university and give back to the place they grew up in.

Zabihullah Arjmand left Afghanistan the same way Safi did — navigating desperate crowds at the airport gates to reach a packed U.S. C-17 aircraft that offered safety.

Arjmand is now with his 3-year-old brother at Fort McCoy. He still feels a sense of loss for those left behind under Taliban rule — including his parents and younger sister.

“It was so hard,” Arjmand said. “It’s the reason more than one hundred people came around the airport and wanted to abandon and desert their country. We saw 2001 again. The American people for 20 years helped us make something and after that everything was destroyed.”

The Taliban are arguably even stronger than they were in 2001 before the original U.S. invasion, some experts contend. In the chaotic American retreat, the Taliban managed to seize some of the high-tech military vehicles and weapons the U.S. used in the region for 20 years. Though the exact cost worth of all the seized weapons is unknown, experts estimate the lost equipment totals billions of dollars.

For Arjmand, Fort McCoy is a safe haven from the new Taliban era — a place that offers a glimpse at a society free from extremist rule. This safety comes with a bittersweet feeling for the refugees, who know their fellow Afghans back home may never experience the same privilege.

“Something that is important for the Afghan people here that is not food, is security,” Arjmand said. “We don’t think something will happen to us. I know there is humanity here.”

Logistical hurdles

The large influx of refugees at Fort McCoy has also come with problems. Shortly after they arrived, food and clothing shortages at the facility left many refugees waiting in long lines for food and wearing the same clothes for days.

Officials said the shortages were mainly linked to supply chain issues and have since been resolved. Refugees like Safi reinforced these claims, noting the conditions are now comfortable.

“In the first days there was a big line for food, sometimes there was no food to get, no clothes or no store to shop for groceries,” Safi said. “But now we hardly [have to] wait four to five minutes to get food.”

Though their living conditions have improved, refugees like Safi are still waiting on clear information about when they will be able to permanently resettle. Local resettlement agencies now wrestle with a lack of language interpreters and affordable housing shortages that have slowed down refugees’ relocation out of Fort McCoy.

Brig. Gen. Andree Carter, who is the U.S. Army representative running the Fort McCoy operation, said all Afghan refugees will be resettled by the end of spring at the latest despite the current delays.

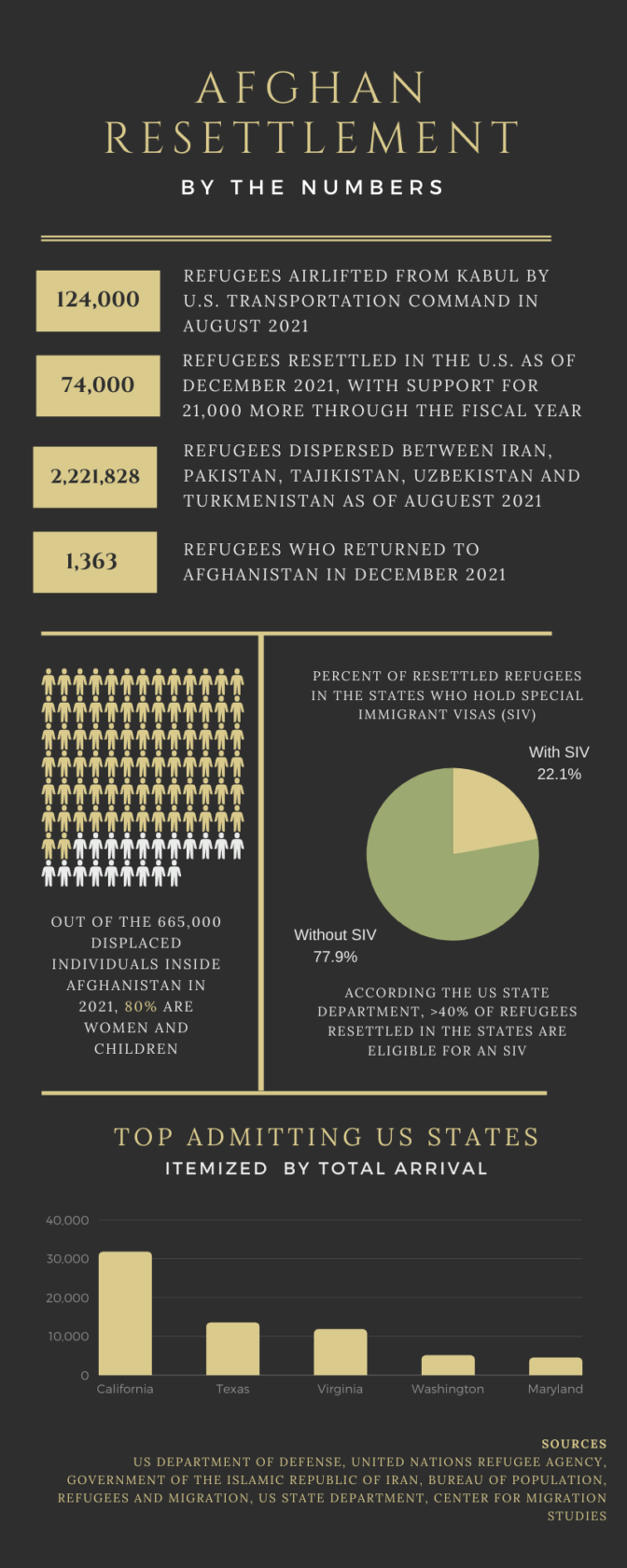

“Resettlement agencies are overwhelmed,” Carter said. “Last year, they resettled 10,000 refugees. With this operation, within a time frame that is less than a year, there are 50,000 Afghans to resettle.”

Resettlement agencies are the primary force helping refugees find places to settle in the U.S. with available employment and legal support. The U.S. State Department is leading this effort by connecting refugees with related agencies after they undergo initial screenings at military bases, according to the State Department Fort McCoy Task Force.

The initial screenings and registration process refugees must undergo prior to resettlement remain difficult, especially with the large number of refugees. Fort McCoy is required to follow various health and government security measures before resettlement can continue.

Officials vaccinated all adult guests at the facility against COVID-19 and various other diseases such as measles. They are now in the process of vaccinating children ages 5-12 for COVID-19. The staff also administers physical exams, records biometrics and holds preliminary interviews with refugees.

The State Department said the primary holdup in moving refugees out of Fort McCoy is finding housing.

“The availability and affordability of housing are a key factor and constraint in a community’s capacity to resettle individuals,” the State Department Fort McCoy Task Force said in an email statement to The Badger Herald. “Temporary lodging is necessary for a period of time, until permanent housing can be secured.”

Some refugees have requested they be sent to specific regions such as Sacramento, Northern Virginia, Austin and San Antonio, the Fort McCoy Task Force said. But services like legal support are limited in these areas and only those with direct family are allowed to resettle in those locations.

These limitations have added to the delays in the resettlement timeline that the State Department and Department of Homeland Security are now trying to speed up. The Department of Homeland Security announced Nov. 8 they would waive application fees and streamline requests for work authorization and Green Cards for Afghan nationals.

But beyond the chain-link fences of Fort McCoy, a renewed Taliban control of Afghanistan still follows those who were not in Kabul — even reaching University of Wisconsin students with ties to the country.

A generational impact

UW sophomore Marjan Naderi is an Afghan-American poet who recently published the book “Bloodline” on her experiences growing up as a child of two Afghan refugees. She experienced the Taliban resurgence through some of her family who still live in Afghanistan.

Many Afghan-Americans in the U.S. directly feel the effects of the country’s trauma over the last half a century because Afghans only started emigrating in large numbers after the Soviet Union invaded the country in 1979.

This leaves younger generations not only with close relatives in a war-torn region — it requires them to cope with their parents’ experiences from leaving the country.

Naderi’s mother is from Herat, Afghanistan — a city located on the west end of the country, opposite of Kabul. Naderi still has family in the region who lived through the Taliban’s recent takeover.

“It was a really intense few days, and we finally woke up one morning and heard the voicemail that the Taliban took over Herat completely,” Naderi said. “I went to Barnes and Noble, and I just cried my eyes out. That was another moment for me where I’m like, the story of Afghanistan needs to be shared.”

Naderi’s aunt, Khala, was still stuck in Herat when the Taliban made their final push toward Kabul in the blitz that completed their takeover of the country. She was able to leave on one of the last American flights out of the Kabul Airport.

The Taliban are now governing Herat with total control over everything from business to prayer. The restrictions infringe on many of the freedoms that temporarily returned to the region in recent years, Naderi said.

“Women and men can’t go to the mosque at the same time, which is absolutely un-Islamic,” Naderi said. “They’re reinforcing traditional wear once again. They aren’t allowing independent civilians to run stores. So overall, the quality of life is not the best.”

Naderi also said the Taliban use intimidation tactics in the city that help them enforce a zero-tolerance policy on crime not seen in the country since the 1990s. In September, armed men hung dead bodies in the city streets who were allegedly killed for trying to kidnap a local trader and his son, though the locals had no way to tell if that was true or not.

“They don’t have access to books and proper knowledge, so they don’t even know what’s going on,” Naderi said. “They can tell you what they report, what they’re seeing, but what they’re seeing can obviously be altered. It could be propaganda.”

The inconsistent control of Afghanistan and its media is not a recent phenomenon. The USSR once ran a communist regime in the country before a series of terrorist groups grappled for power during the U.S. presence in the region.

A historical precedent

The Taliban started in Afghanistan almost 30 years ago, toward the end of the Cold War. A covert CIA operation trained Mujahideen fighters, a series of Islamic guerrilla groups who practice jihad, to help topple the Soviet regime in Afghanistan.

Mohammed Omar was one of those fighters. Omar trained alongside other notorious names like Osama Bin Laden, who is credited with orchestrating the 9/11 attacks. Omar created a small militant group that ultimately became the Taliban known today.

Mou Banerjee, a UW professor of Southeast Asian history, said Omar’s Taliban emerged during that period of absent political leadership in the country.

“[When] the Soviet regime leaves Afghanistan, there is a period of infighting and civil war that starts,” Banerjee said. “And there are four or five ethnic groups, essentially, with particular ideologies of their own, who start thinking about the future of Afghanistan.”

Omar established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in 1996 following this period of turmoil. He ushered in the most strict enforcement of Sharia law — Islam’s legal system — from 1996 to 2001.

Under the Taliban’s interpretation of Sharia law, women were forced to wear burqas and men had to grow beards, while schools for girls were closed. Taliban police performed public executions of Afghan civilians and denied food supplied by the UN.

Following the 9/11 attacks that brought American military forces to Afghanistan, the U.S. presence in the country ended this radical rule and returned functions like female education to the region. Since 2001, the Taliban’s enforcement of Sharia law has been more of a fear than a reality for the Afghan people, according to Banerjee.

It is uncertain whether the Taliban will return to their strict 1996 ruling style after their recent takeover. Taliban public relations officers have claimed they will create a more structured, less extremist government that provides rights to women and religious minorities.

But the current Taliban cabinet is largely composed of the founding members of the Taliban who were in charge during their most aggressive period of rule from 1996 to 2001. Many of these members are named on blacklists of the UN and FBI. The return of all-too-familiar faces has left women and religious minority groups uneasy about the restored Taliban regime.

An uncertain future

One group this renewed Taliban power threatens is the Sikhs, who the Taliban have historically discriminated against over religious conflict. Following the Soviet retreat from Afghanistan in the 1990s, a civil war broke out and jihadi groups destroyed seven Sikh temples — referred to as gurdwaras — and a primary school.

The Mujahideen and Taliban destroyed Sikh businesses and looted their temples in the country. This choice is believed to be linked to them grouping Sikhs in with Hindus who destroyed a Babri Mosque in India in 1992. The Taliban has also historically forced Sikhs and Hindus to wear yellow armbands and hang yellow flags over their homes.

UW freshman Amanpreet Sehra is one of the founders of SikhTeens, a growing blog designed for Sikh youth to explore Sikhism in a safe online environment. For Sehra, the Taliban takeover became personal when Taliban leaders began discussing with Sikh leaders in the country.

“They met with the minorities to kind of show that ‘Hey we respect our minorities,’” Sehra said. “Everyone was like ‘Oh, this is scary. This could just be a photo op. They could just be taking this picture and sharing it to make us believe that they’re safe.’”

Recent estimates predict about 140 Sikhs remain in the country — including some who were unable to board India’s evacuation flight after an ISIS-linked suicide bomb attack near the airport. In October, some were still waiting for commercial flights to resume flying out of the country to leave for cities in India, Europe and Canada.

The Taliban have almost no funding to run the government they argue will restore various human rights for women and end terrorism towards minority groups like the Sikhs. The International Monetary Fund froze all Afghan assets in the Afghan national bank, essentially crippling any government function in the country.

“That means for many months now, ordinary Afghan people have not been paid,” Banerjee said. “Schools and hospitals and banks are not functioning. Food will run out there before winter starts. What we’re looking at is widespread starvation.”

That widespread starvation is currently underway, with 23 million Afghan people facing severe food insecurity. The Taliban have been unable to provide food to the Afghan people. They blame the U.S. for freezing nearly $9.5 billion in Afghan Central Bank assets when the Taliban took over in August.

The U.S. recently loosened those sanctions by expanding the Treasury Department’s general licenses that will allow more aid groups to work in Afghanistan. The United Nations Security Council also passed a resolution that will grant humanitarian exceptions to sanctions on the Taliban.

In January, the UN launched an unprecedented appeal for more than $5 billion in humanitarian aid, which would help over 22 million Afghans in the country and 5.7 million refugees in neighboring countries. But donors remain wary about providing money to the country given the uncertainty about the Taliban’s rule.

It is also unclear how effective aid groups will be able to tackle the starvation crisis even with streamlined international support. Many have left the country because of Taliban security threats, and those remaining face worker shortages. Beyond the dire situation of the country’s economy and food supply, Afghans must also face the reality that Afghan culture may be overwritten by a new wave of extremism.

Domestic and international cultural suppression

The total return of Taliban rule in Afghanistan threatens the rich culture that once blossomed freely before strict regimes gripped the country.

Nelofer Pazira-Fisk is an Afghan-Canadian director, actress and journalist who lived in Kabul as a child under Soviet occupation. She said she sees similarities between the cultural scene during the USSR control and the one now under Taliban rule in a panel on Afghan women and art hosted by the UW Center for Middle East Studies.

“We did live under a police state in that kind of a context of a so-called communist regime,” Pazira-Fisk said. “Art and culture was perceived as a tool in the hands of the authorities and there was censorship. [Today,] journalists are being detained and music is banned again, [and] the number of women participation in public is reduced.”

Afghans make up one of the largest shares of international refugees in the world, with 2.6 million registered Afghans living in the world and another 3.5 million displaced within the country who are still searching for new homes.

This trend — though bringing Afghan culture to places around the world — also divides the country. Pazira-Fisk said while many Afghans successfully end up working for local TV stations or newspapers sharing their stories in their own language, they are still haunted by the political and economic status of Afghanistan.

Afghans around the world are united in the suffering Pazira-Fisk describes, where they live a double life in their new country still struggling with their homeland being destroyed by the Taliban.

The solution to the perpetual problem of extremism and outsider interference is unclear. As Zabihullah Arjmand said, a 20-year U.S. campaign in the country had almost no effect on the Taliban’s power. The Taliban also has no history of providing a structured government with a free society and economy.

Aid groups have been able to supply the Afghan people with necessary goods and services amid war conflict for years. But now, even that humanitarian safety net is threatened. The Taliban resurgence has so far left the future of Afghanistan in the air.

Since military tactics have rarely worked to resist extremist groups, some refugees like Rahim Safi see a grassroots approach as the only option.

“The only thing that can change Afghanistan is education,” Safi said.

While widespread education is hard to imagine under strict Taliban rule, Afghans do have a global presence that helps push organizations like the UN to challenge Taliban leaders. Some Afghans hope this unity will eventually lead to reform in the country. Even if it is incremental, every step forward counts for the people who love Afghanistan.

“Afghanistan is the merging ground of so many cultures and ethnicities and so our art is so incredibly rich,” Marjan Naderi said. “But it all boils down to the central core of love for each other.”