When Brett Ranon Nachman, a doctoral student in the Department of Educational Leadership and Policy Analysis at the University of Wisconsin, entered graduate school, he noticed the campus’s lack of resources available to students with Autism Spectrum Disorder.

As a college student with Asperger’s, this was upsetting to him. Nachmon said UW is not alone — his research has found that most higher education institutions are not accommodating of students with ASD.

Emily Raclaw, Director of On Your Marq, a new organization at Marquette University that supports students with ASD, said while the transition to college is difficult for many students, it can be especially jarring for those with ASD.

From navigating independent living to learning in overcrowded classrooms, many aspects of higher education can hinder students with ASD’s learning, according to Raclaw, who said these obstacles are difficult to overcome without support.

Dwindling support

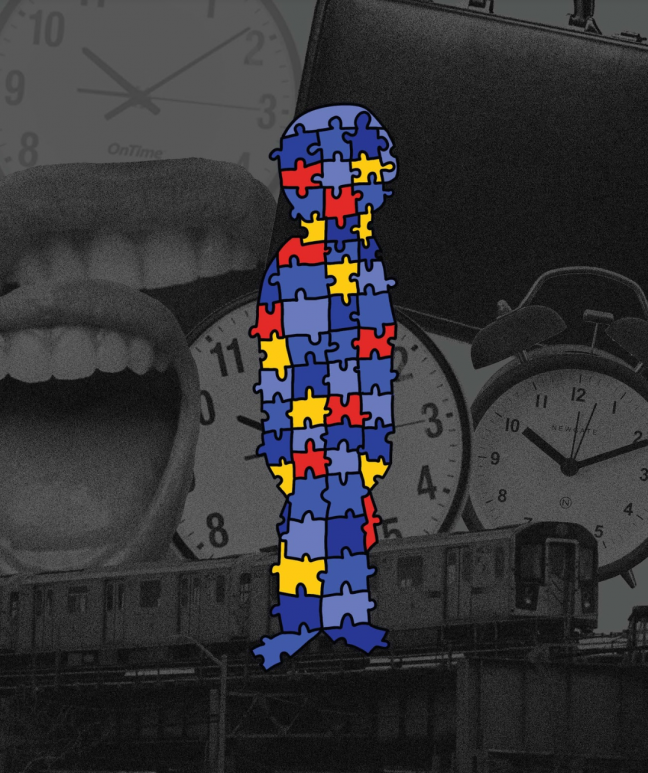

According to a report published by the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, there is a decrease in all support services for adults with ASD after high school. The report found that at age 17, 58% of individuals with ASD receive social work services. But, , after high school the same is the case for only 22% of individuals with ASD. A similar decrease occurs for individuals who receive personal assistance services after high school.

This drop in support is even greater for adults pursuing higher education. According to a report on post-high school outcomes for adults with disabilities published by the National Center for Special Education Research, only 19% of higher education students with a disability received any accommodations for their disability from their schools. While the report found that 87% of high school students with a disability received accommodations.

This report also found that 54% of students with ASD who did not receive any help with schoolwork thought assistance would have been helpful.

Listening to students with ASD and understanding what their educational needs are is key to creating learning environments that are accommodating for everyone, Nachman said.

“We [must] work towards not just autism awareness but also autism acceptance,” Nachman said. “Acceptance comes from understanding, but ultimately acceptance doesn’t happen until we really hear and see the merit in what autistic individuals have to say.”

Hearing from individuals with ASD and being accommodating of their needs is important at Yahara house, a non-residential clubhouse that offers work experience and mental health support for adults. Lead Clubhouse Specialist at Yahara House Micheal Weinberg said they work to ensure they are inclusive of everyone’s needs, which is important as many people with ASD have multiple conditions affecting the support they receive.

Weinberg said though Yahara House only works with adults who have mental illness many of their members often have multiple co-occurring conditions such as ASD. The many environmental stressors individuals with ASD face can make them more likely to also experience mental illness, Weinberg said.

Yahara House works with these co-occurring conditions by providing meaningful work for members that may help them find outside employment later on. This support is important, especially for members with ASD, as historically, resources for individuals with ASD have been geared towards children, according to Weinberg.

Weinberg said increasing support for adults is crucial as autism diagnoses are steadily on the rise, with about one in every 59 children diagnosed with ASD in 2014, a leap from one in every 150 in the year 2000, according to the CDC.

“If you are getting services as a child and you no longer get any support when you are an adult, that’s not gonna go well … after about college-age, it drops off precipitously,” Weinberg said. “I think there just needs to be places where adults who have autism, regardless of their place on the spectrum — but especially for folks who would like to get into work — would like to build community, have a place to go.”

This focus on adult care is also important for people who are diagnosed later in life, said Adam Brabender, the co-chair of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin’s newly formed Disability Caucus and Yahara House volunteer and former member.

Brabender, 43, was not diagnosed with ASD until he was almost 20. He had struggled with anger issues, often getting him into trouble, but now has two therapists who are specifically trained for working with individuals who have autism.

Brabender said the drop in care for adults with ASD can lead to individuals not receiving the services they need, such as health care or support with academics and employment.

The Yahara House is working to close this gap in adult care. Megan Walsh, Yahara House’s youngest member and a student studying early childhood education at Madison Area Technical College, said Yahara House has supported her through school by offering homework help.

While academic support is crucial, Nachman said higher education institutions should also make systematic change. He said implementing a universal design approach to learning could improve accessibility.

“Accommodations and disability service offices are not necessarily designed for autistic students,” Nachman said. “A universal design for learning is basically principles that say what supports one student in their individual success may actually help a lot more students.”

Nachman said accommodations that may be beneficial to students with autism include individual coaching, peer mentoring and sensory-friendly classrooms. Additionally, realizing group work can be anxiety-inducing for some students, letting students express knowledge in creative ways and giving students more of a voice in how they learn overall could be beneficial, Nachman said.

Raclaw said one way OYM supports students with ASD is by informing instructors of the power imbalance between them and students. She said instructors need to know that when students share their accommodation letters, they are not asking for special treatment, but simply sharing their individual needs.

While OYM guides students throughout college, Raclaw said support with the transition into college is key.

“People think that since we did all this front-loading when they were younger that they will be fine when they are adults,” Raclaw said.

Need for higher education programs like OYM is rising. According to the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute report, in 2015 36% of adults with ASD attended a postsecondary institution. Of those students who chose to disclose their disability to their postsecondary institution, only 42% received accommodations.

Medicaid, influx of ASD diagnoses

Demand for other adult-centered resources is also increasing. According to a study conducted by Postdoctoral Fellow at the UW Waisman Center Eric Rubenstein and Assistant Professor in UW’s School of Social Work Lauren Bishop, ASD in children has increased by over 200% in the past two decades. Their study said that as this population ages into adulthood, more adult-centered resources will be needed.

These adult-centered resources include accessible medical care. Rubenstein and Bishop’s study tracked the Medicaid enrollment patterns of Wisconsin adults with ASD from 2008 to 2018.

According to the report, these findings show a recent significant influx of young adults with autism into the Medicaid system. Their findings showed that about 73% of the Medicaid claims they studied were made by beneficiaries who had entered the Medicaid system after 2008 — most under the age of 30.

Medicaid is the nation’s public health insurance program for people with low income, providing health coverage to 64.7 million people nationwide. Medicaid plays an especially critical role for the disabled population. It covers 48% of children with special health care needs, 45% of non-elderly adults with disabilities and more than six in 10 nursing home residents. Eligibility is determined by income caps that are decided by states.

In Wisconsin, Medicaid services for people with disabilities includes a wide range of support and services. These programs help people pay for both medical coverage and prescription drugs, according to the Wisconsin Department of Health Services.

Medicaid resources become even more important as individuals age because people with ASD have an increased risk of age-related health issues such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease, the Waisman study said.

The report also found that older individuals use Medicaid resources more frequently, as beneficiaries with ASD who were over age 60 had the highest number of visits at 23.2 per year compared to 9.3 per year for beneficiaries in the 21-29 age range.

“With autism in particular, we see that as people age, like everybody, they’re dealing with physical health problems,” Bishop said. “Then, because they have autism and because of the lived experience of having autism — which can include being discriminated against or having poor access to health care — they are dealing with more physical health problems.”

The increase of individuals with ASD enrolling in Medicaid could lead to barriers in care such as delayed diagnoses and long waitlists, the report said.

Different Medicaid programs have different income limits that determine eligibility. Brabender said these income caps are too low and do not allow people to work and still receive benefits.

“There is no incentive for people to continue to work under the program as it is currently. We as a society expect people to work and not live off the taxpayer’s dime. There needs to be a better system in place, such as work incentives, and not penalize people for working,” Brabender said.

If people are not eligible for Medicaid, they might not see the doctors and specialists they need, resulting in the use of emergency room services and case-management services, Brabender said.

Rubenstein said people on the edge of the income requirements that have the ability to work are the ones most affected. Those who earn close to the income cap are faced with the hard decision of being employed and potentially losing their Medicaid benefits and being unemployed and having less income.

Bishop said this decision is made more complicated because many people with developmental disabilities want to be able to work in meaningful ways.

“People are sort of in a catch-22 because they don’t want to lose their insurance benefits,” Bishop said. “Part of being human is wanting to work in an environment where you feel like you can be making a contribution and using your skills.”

This desire for meaningful work is realized by the Yahara house, where they work alongside members and help them connect with jobs outside of the clubhouse.

Yahara House Director Brad Schlough recalled one day when he was the first staff member to arrive — there were already six members waiting at the door. Once he unlocked it, they all went to work immediately. This desire to work sometimes forces members to choose between having a job and remaining clubhouse members as they either have to be on a Social Security supplement or Medicaid, according to Schlough.

Public Policy Analyst and Legislative Liaison for the Wisconsin Board for People with Developmental Disabilities Tamara Jackson said many of the services and supports people with ASD need are only available through Medicaid.

“Medicaid services are important because without them, families often become the case managers,” Weinberg said. “This is not an ideal situation as families are not trained professionals, and it puts a lot of pressure on them.”

Brabender said he is trying to ensure better policies regarding Medicaid and general support for people with ASD through his work with the disability caucus. People with disabilities are severely underrepresented and politicians often do not talk about the issues that affect them, Brabender said.

Self advocacy, inclusion

The ASD community is a voice that has often been excluded from policy decisions, which can be particularly detrimental when it comes to policies that directly affect them, Brabender said.

Brabender said his identity as both a gay man and someone with ASD has been a struggle — one that has inspired him to encourage individuals who are gay and have disabilities to participate in government, both as advocates and elected officials.

Including the ASD community in all decisions that involve them is the only way to ensure adequate accommodations are made, Jackson said.

“If you have people who are making all of the decisions who don’t actually know what’s important to the people who are living with those decisions, that is likely to result in a system that is not really meeting the needs of the people who rely on it,” Jackson said.

Weinberg said that people with ASD have historically not been listened to by politicians, regardless of party.

It can be hard for people with ASD to make themselves heard because the system often gets impatient with them, Schlough said. Even medical professionals often talk to Yahara staff instead of the member being treated because they are not trusted to represent themselves, Schlough said.

Because the system is not accommodating to people with ASD, inviting people to the table is not enough, Nachman said. We must ensure self-advocacy is also made accessible to all people.

“We can’t continue this trend where other people are making decisions for or speaking for people in the autism community,” Nachman said. “It’s absolutely essential to include everybody in the conversation, and more importantly, to have many avenues for speaking those inputs. Not every autistic individual, like many individuals for that matter, would feel comfortable sharing their thoughts in a public forum.”

Making self-advocacy more accessible is not limited to policy decisions. These accommodations are also important in the classroom.

UW’s McBurney program focuses on ensuring instructors know how to make their classes more accessible and empowering students with disabilities. One new program they have developed to do this is AS WE ARE — Autism Spectrum Well-being, Education, Aspiration, and Relationship Empowerment. AS WE ARE is a group for students with ASD to connect with each other.

Programs at higher education institutions that give students with ASD a platform to speak, like AS WE ARE and On Your Marq, should not be few and far between, Raclaw said.

“While it’s great to pretend we cornered the market on something, I want people to have options. One of our students said it best. He said every college needs this kind of program,” Raclaw said.

Support for adults with ASD is on the rise with the emergence of these new adult-focused programs and efforts to increase support for long-standing ones like Yahara House.

Bishop said the Waisman report is an important first step in the shift to adult-focused care.

“We’re at the point where this research is only a really basic initial step. What I hope will come from this is, I hope that the research field coalesces around trying to better understand the healthcare needs of adults on the spectrum so that we can determine whether we need to develop specialized programs,” Bishop said.