For many Badgers, Camp Randall is hallowed ground. The stadium’s aluminum bleachers hold decades of history, steeped in football fanaticism and intimately linked with the college experiences of thousands. But the area’s significance extends beyond the gridiron.

In 1858 the lands served as the Wisconsin State Fair grounds, and would later be used to host the Barnum Circus, as the site of research facilities and for veterans’ housing. Noteworthy among these chapters of history is its role during the Civil War, during which the grounds became known as Camp Randall, a barracks for Union troops and a prison camp for captured Confederate soldiers.

Imprisoned at Camp Randall

Following the Battle of Island No. 10 in April 1862, the victorious Union forces found themselves in charge of an estimated 7,000 Confederate prisoners in need of transfer to Federal prison camps. James Herberling, author of “The Boys at Forest Hill,” wrote that in early April it was announced that Madison would receive roughly 1,000 of these prisoners. They were to be held at Camp Randall, then a training grounds and barracks established by Wisconsin Gov. Alexander Randall the year before.

Camp Randall received little notice of these captured Confederates, and was subsequently under-equipped to accommodate such a volume of prisoners. Despite the conditions, Camp Randall was able to provide reasonable conditions for the captives. Arriving Confederates received medical care and regular army rations, supplemented by provisions such as fresh milk and tobacco donated by Madison citizens. They spent their days idly, under guard of the 19th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

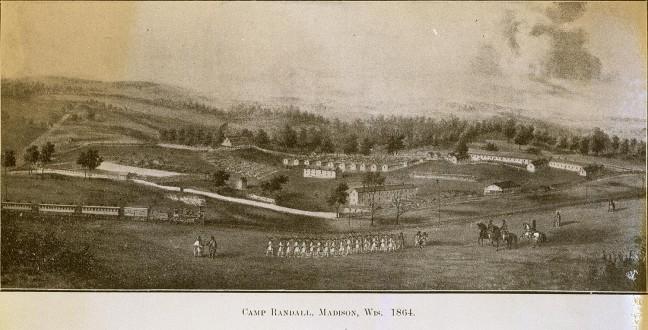

Photo courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society

Despite best efforts, U.S. Army officials deemed camp conditions unsuitable. A May 1 letter written by Assistant Quartermaster J.A. Potter described the soldiers of the 19th Wisconsin as undisciplined, inexperienced and poorly-equipped to guard such a volume of prisoners. He expressed disappointment in hospital conditions, noting that of the roughly 1,200 prisoners held at Camp Randall, some 200 were hospitalized with illness.

The condition of these afflicted prisoners worsened. Despite medical care, more prisoners began to succumb to measles, mumps and pneumonia. A Private Paddock of the 19th Wisconsin Regiment wrote to his family regarding these deaths: “They die off like rotten sheep. There was 11 die off yesterday and today, and there ain’t a day but what there is from two to nine dies.”

“They die off like rotten sheep. There was 11 die off yesterday and today, and there ain’t a day but what there is from two to nine dies.”

Barely a month after their arrival at Camp Randall, the Confederate inmates had to relocate. President Abraham Lincoln’s call for a larger fighting force drew the 19th Wisconsin Regiment back to battle, rendering Camp Randall unsuitable for securely holding prisoners. On May 31, 1862, the majority of the Camp Randall inmates left for Camp Douglas, a larger encampment in Chicago.

By June, the last of the Camp Randall prisoners had left. The only ones who still remain in Madison are 140 Confederate soldiers who died during their stay at Camp Randall, now interred at Confederate Rest.

The boys at Forest Hill

Dead Confederate prisoners were buried at Forest Hill Cemetery. Initially grouped into a mass grave, the dead were later given their own headstones and a more formally organized plot, now known as Confederate Rest.

The plot is well-shaded and removed from the more populated areas of the cemetery, a quiet and somber reminder of an unsung chapter of Madison history.

The Guard House

All that remains from this chapter of history is a small wooden structure along Monroe Street referred to as “The Guard House.” Drab and unassuming, the squat wooden shanty sits sheltered under a compact metal pavilion. Though the structure traces back to the Civil War-era Camp Randall, its exact origins remain unclear. The structure dates to Camp Randall’s Civil War period, but the details of its construction and location are uncertain.

What remains today is reconstructed from a larger original building, which was likely used as a detention facility for soldiers. Whether this housed captive Confederates or if it exclusively served as a disciplinary holding cell for Union soldiers is unclear.

A Madison citizen purchased the structure at auction when the war ended, converting it for use as a granary. No exact records of the structure exist beyond this event, but the building reappeared in the Camp Randall Memorial Park at some point between 1914 and 1936, a lasting relic of Madison’s Civil War history.