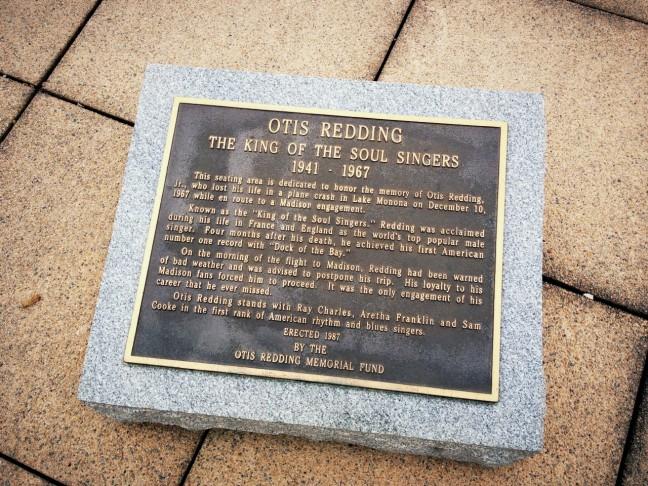

Almost exactly 47 years ago, music legend Otis Redding died after his plane crashed in Lake Monona. Now his memory is eternalized through a plaque in front of a marble bench on the roof of Monona Terrace. The heading reads, “Otis Redding, The King Of The Soul Singers 1941-1967.”

The incident occurred Dec. 10, 1967 at 3:28 p.m., approximately three miles from the landing strip at Madison Municipal Airport. Among the deceased were five young members of Reddings’ backing band The Bar-Kays: Phalon Jones, Jimmie King, Carl Cunningham, Matthew Kelly and Ronnie Caldwell. The pilot of the plane Richard Fraser also died in the crash.

The only survivor was the trumpet player of the Bar-Kays, Ben Cauley, who was 20 years old in 1967. He woke up in the airplane feeling the sensation of falling, Cauley said. His next move may have saved his life.

“I reached down and unbuckled my seat, I don’t know why, I just reached down and unbuckled it.”

Cauley was not able to swim and had to grab onto a seat cushion to stay afloat. He remembers hearing the cries for help of Caldwell, 19, and Cunningham, 18, but was unable to reach them. All victims of the crash went down with the aircraft. Newsreel footage from the time shows the recovery of Redding’s body from the lake, pulled from the water still strapped to his seat.

No official reason for the crash was ever released. The aircraft was a twin-engine Beechcraft plane, purchased from singer James Brown by Redding only a few months prior. Brown is reported to have warned Redding against using the aircraft. Weather conditions Dec. 10 were less than ideal, cold and foggy with a light drizzle. Air traffic controllers reported that the pilot indicated no problems with the flight as late as 3:25 p.m., three minutes before the plane went down. They never received any messages from the pilot suggesting otherwise.

All theories regarding the cause of the crash are best guesses. Some say the pilot mistook his distance from the runway due to the fog and realized after it was too late. Others say the plane lost power for some reason and that’s why it went down. A Capital Times report from the day after the crash said Cauley described hearing a mechanic tell the pilot a day before about problems with the plane’s battery. This would support the theory that the plane lost power, but again, nothing could ever be confirmed.

Redding and The Bar-Kays had taken off from Cleveland and were en route to Madison for a show that night at The Factory, a club located at 315 W. Gorham St. (just off State Street). Concertgoers began lining up late in the afternoon. Jim Danky was among them, his group having arrived to the show early hoping to get spots close to the stage.

Danky shed some light on what Redding’s notoriety was like among college-age Wisconsinites at the time.

“[It was] less common for people to listen to music across racial divides,” Danky said.

Danky recognized this was an unfortunate reality for the 60’s music scene and one that still applies today in some ways.

Redding was only beginning to find a mainstream audience in ‘67. A black R&B artist out of Macon, Georgia, Rolling Stone referred to him as the “Crown Prince of Soul.” He was signed to Stax Records out of Memphis, Tennessee. The city had a growing reputation as a mecca of soul music, which led to a request from The Beatles to record there. The deal leaked and “Beatlemania” made recording in Memphis impossible, but the request is indicative of the notoriety of Stax at that time.

Redding himself was coming off well-received performances in Europe and at the Monterey Pop Festival. The popularity of these shows had given him access to white audiences that dominated mainstream music. White performers released all of the top ten songs on Billboards’ year-end chart for 1967. Aretha Franklin is the first black artist to make the list at No. 12 with “Respect,” a cover of a song written by Redding.

He had recorded the song “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay” just three days before the crash. It had more of a pop feel than what many of his contemporaries in the Memphis scene were used to, but Redding believed it could serve as a crossover between R&B and pop listeners. He was right. The song would be released posthumously in 1968 and skyrocketed to the top of both the pop and R&B charts, eventually landing at No. 4 in Billboard’s year-end rankings. Redding was only 26 years old when he passed.

The Factory’s owner Ken Adamany was anticipating Redding’s arrival when he received multiple calls from police asking if the venue was expecting an “orchestra.” After some confusion, the miscommunication was cleared with another call.

“Then we got a call asking if we would come down and identify the bodies, at that point we figured it out,” he said.

Gary Karp, a member of a popular local act The White Trash Blues Band, was sent to the second floor with a megaphone by police to tell the crowd outside what had happened.

“The response was a lot of boo’s and ‘BS’ and ‘I bet he was never booked to come here anyway’ … [It was] a period where people thought music should be free, there was a lot of distrust as far as ‘you’re charging too much,’ not just [The Factory] but for shows in general,” Adamany said.

The police were afraid of a riot. An R&B group called Harvey Scales & The Seven Sounds flew in from Milwaukee to play a free show with the hopes of quelling tensions.

Cauley went on to have a successful music career as a trumpet player. This included a temporary reformation of the Bar-Kays with original member James Alexander, who had taken a commercial flight to Milwaukee on the day of the crash due to the Beechcraft’s 8-person capacity. Cauley would return to Madison for the first time in 2007 for the 40th anniversary of the crash and sing a rendition of “(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay)” as a tribute to Redding and his bandmates in The Bar-Kays.

The plaque at Monona Terrace serves as a reminder of Madison’s tragic place in the history of R&B music. From its perspective, the lake looks a bit more ominous.