In May of 1969, Doug Bradley wasn’t expecting Uncle Sam to notice his graduation from college. Nonetheless, the United States Army sent him a letter to acknowledge the event: Graduate school was no longer grounds for military deferment.

Now that Bradley was no longer a student, he was eligible for the draft and could be deployed to Vietnam. Depending on where his birthday ranked in a lottery played with 366 plastic balls, it might be the coming winter, or so far into the future the war might already be over.

June 7 became an unlucky number that year. Bradley’s birthday was the 85th ball to be drawn. He would be shipped to eight weeks of basic Army training in March 1970. Vietnam followed that November.

“It’s sort of an interesting way to celebrate your graduation from college,” Bradley says.

Bradley – a native Philadelphian born to an Italian mother – left the Delaware Valley to attend Bethany College in West Virginia. After serving in Vietnam in 1970 and 1971, he eventually came to Madison, where he currently lives. Today, Bradley releases his first book “DEROS Vietnam: Dispatches from the Air-Conditioned Jungle.” His collection of short stories represents a fictionalized account of his experiences serving as an Army journalist during the Vietnam War. Tonight, Bradley will be reading selections from his book as part of the Wisconsin Book Festival.

The book title, “DEROS,” comes from a military acronym, which stands for “Date Eligible for Return from Overseas.” Bradley says “especially in a god-forsaken place like that – that kind of war – your DEROS date was sacred.” The two dates bookended soldiers’ 365-day tours of duty.

“When I got there on Nov. 11 … I knew on Nov. 11 the following year – that was my DEROS date. And I was gonna be, hopefully, home safe and sound,” Bradley says. “There were guys who counted down from 300 or 200 [days]. I wouldn’t do that. I thought I’d go crazy if I knew I still had 199 days left in Vietnam.”

Bradley served in Vietnam toward the war’s end. During America’s withdrawal, President Richard Nixon euphemistically referred to the transition of military control from American to South Vietnamese hands as a process of “Vietnamization.” Bradley says, “It really was sort of deceitful because the war was still hot and escalating.

“For us it was an air war. For the South Vietnamese, it was a ground war.”

Bradley recognizes the serendipity of his deployment to the Army headquarters at Long Binh Post, where he served as an editor in the Army Command Information Division. Because of their seeming cushiness and distance apart from combat zones, his offices were colloquially referred to as the “Air-Conditioned Jungle.”

“It was a huge relief. Cause even though the war was winding down – it was still a war,” Bradley says.

At Long Binh, Bradley edited the weekly newspaper, called the Army Reporter, as well as the Army’s UpTight magazine. “I would write cut lines for photographs, I would crop pictures, I would lay out the paper and edit the stories,” he says.

Later, Bradley started drafting news reports about military units in the field. With his Army correspondent card, he traveled the country collecting material for stories at his superior officers’ instructions. “They would say, ‘We need another story. Go out and do this.'”

After the 1969 My Lai Massacre, in which US Army soldiers executed between 347 and 504 unarmed Vietnamese civilians, the Army was anxious to sanitize the wartime press. In its propaganda effort, the Army censored its reporters’ stories. “I didn’t write what I saw,” says Bradley.

As a way to broadcast positive impressions, Bradley’s superiors occasionally scrapped news articles. He recalls one instance in which he profiled a trainee in the South Vietnamese army.

“We wanted to write a story about how they were taking over the war and how well they were doing,” he says.

“The interesting thing was, I was supposed to pick this kid up at two intervals. One, when he was first in basic training, and later … when he was in the field, in combat doing the job he was being trained to do – taking over the war we wanted the [South Vietnamese] to take over.”

After the publishing the first part of the story, Bradley returned to conduct a follow-up, weeks later.

“This kid had gone AWOL. He was gone, nobody could find him. And when I pressed the people who were helping me, … they didn’t tell me … about half of that unit had deserted,” he says. “[The South Vietnamese] didn’t want to fight this war either.”

Based upon his follow-up inquiry, Bradley’s superiors didn’t run the story’s second half.

Bradley’s flight back to Philadelphia came in November of 1971. He returned, unwounded, but carrying the weight of Vietnam’s stories. His burden was one of words.

“I didn’t have to think about having killed somebody. I didn’t have to think about somebody being killed because I didn’t do something,” he says. “Well, I didn’t tell the truth. And I was part of something that I probably didn’t want to be a part of. I’ve learned to live with that.”

Bradley wants his work to convey the stories of the soldiers who served from the back of the Army lines. These veterans served in a different, but no less significant war front.

“We know about the blood and guts. We know the heroes and the not-so heroic. But the majority of guys who served in Vietnam were in jobs like mine,” he says. “They were in the rear. They weren’t out in the field, they weren’t combat soldiers.

“There were almost 3 million of us.”

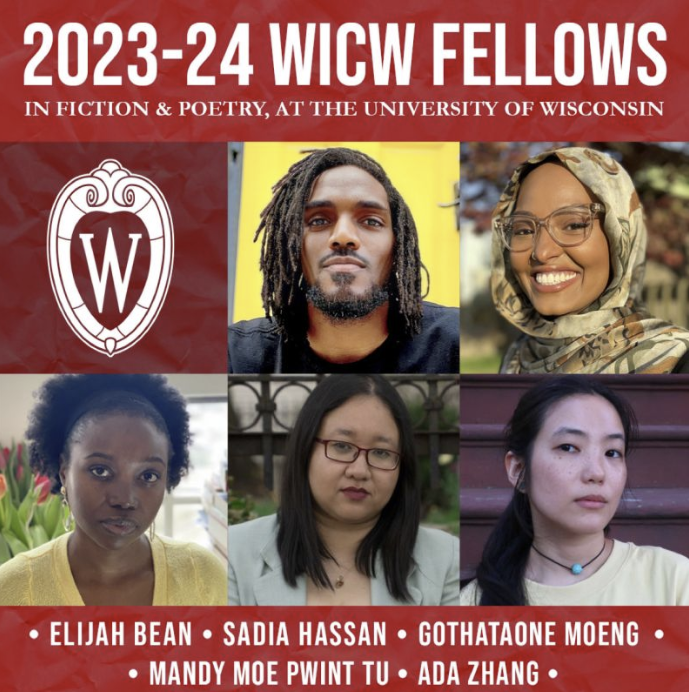

To celebrate the completion of 40 years of writing “DEROS Vietnam,” Doug Bradley will be hosting a cake reception starting at 5 p.m. Wednesday, Nov. 7, at A Room of One’s Own Bookstore (315 W. Gorham St., formerly Avol’s Bookstore). In conjunction with the Wisconsin Book Festival, Vietnamese author Lan Cao, will join him to read from her book, “Monkey Bridge,” at 5:30 p.m.