Pussy Riot’s debut as an anti-Putinist, feminist punk rock band took Russia by storm, and global eyes watched in both amazement and support.

Two of the 11 members, Maria (Masha) Alyokhina and Alexandra (Sasha) Bogino, brought their stories and insight to a Q&A discussion panel at Memorial Union Thursday.

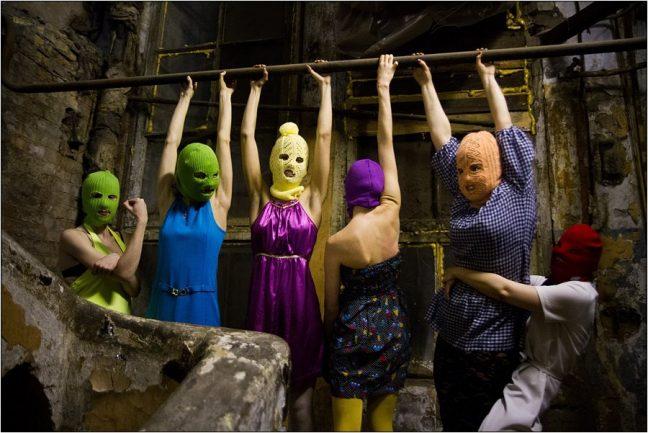

Pussy Riot gained both local and international attention through their acts of unauthorized guerrilla-style performance art, often provocative and rather shocking in nature.

Sporting full masks and punk rock attire, their performances often targeted themes of feminism, LGBT rights and opposition to Putin’s reign. They took place in culturally or politically significant places, such as Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, where three members of the group were initially arrested in 2012 for “hooliganism.”

While two of the women in Pussy Riot faced imprisonment in inhumane conditions, it did little to silence them. If anything, imprisonment opened their eyes further to the catastrophic problem of Russia’s prison system — and to the much larger problem of President Vladimir Putin’s dominance over Russia. It willed them to fight harder.

Joined by their tour manager, Alexander Cheparukhin, who served as a moderator for this discussion, the presentation began by a brief overview of the group’s current activities and human rights efforts. The most notable was the co-founding of the influential human rights news service, MediaZona. MediaZona serves as an independent check on law enforcement and government that aims to fill the information gap created by state-owned media.

Beforehand, no such organization existed in Russia. Now, it is one of the most influential mediums, according to Cheparukhin.

Alyokhina and Bogino began the presentation with a 13-minute Pussy Riot documentary trailer that depicted the groups’ actions as protest art, and is comparable to the long-standing tradition of such in Russia which spans all the way back to the times of Ivan the Terrible and Peter the Great.

This set the tone that Pussy Riot’s actions were entirely political and serious in nature, and they should not be written off as just another punk rock group.

“They were probably the first artists [in Russia] in prison for their political art,” Cheparukhin said.

The group spoke extensively on the imprisonment Alyokhina endured in the penal colonies — small prison villages of around 1000 women. There are no cells but instead barracks where around 100 women share one room and two bathrooms.

“I came to this penal colony, and what I saw was quite shocking,” Alyokhina said.

Women in these penal colonies are often given insufficient or even rotten food and only get the opportunity to bathe approximately once a week, Alyokhina said. What was most shocking to Alyokhina, however, was the fact that the women in this prison were required to work between 12 and 14 hours a day, sewing uniforms for the Russian army.

Appalled and outraged by the conditions in the prison, Alyokhina found a way to bring these issues to the attention of her lawyer. She was then put into solitary confinement.

“I had no choice but to fight back,” Alyokhina said.

While confined in the prison, Alyokhina participated in any means possible to bring attention to the prison conditions, including a hunger strike. While complaints made by inmates against administration are often “blown off,” Alyokhina was relentless.

“Nobody else made the process … against violations inside the prison so loud and so public,” Cheparukhin said.

Alyokhina and her lawyer went on to win three out of four trials in court against the prison administration.

She owes these victories largely to the support of the global community and the fact that she had the public’s eye watching her throughout her incarceration.

“The most, I think, incredible thing that came out of our case is the support which we received from around the world,” Alyokhina said. “The support gave us safety inside the penal colony.

Alyokhina and the group went on to explain how, in many circumstances, prisoners who attempt to fight against the prison administration are resisted and sometimes even discreetly killed.

But because of the public attention for Pussy Riot’s case, the women had safety and a voice inside the penal colony.

The group went on to give advice to the American audience after a question was proposed about what activists and citizens can do in light of recent President-elect Donald Trump.

“Stay together because together you have a voice, which is stronger,” Bogino said.

The women of Pussy Riot encouraged the audience to stand together and acknowledge the deeply rooted connection between artistic activity and human rights work.

“If you will not fight for your democracy — if you will not really believe in it — you will lose it,” Alyokhina said.