In February of 1969, first-year law student Geraldine Hines sat alone on the steps outside the University of Wisconsin Law School. As one of only four Black students in the entire law school, Hines was boycotting classes in solidarity with 13 demands made by Black students to address inequities at UW.

Even when a UW administrator approached her and said it was “undignified” for a law student to participate in the campus-wide demonstrations, Hines stood firm on the steps as part of the 1969 Black Student Strike that united thousands of students in protest.

More than 50 years later, UW junior Juliana Bennett sat on a Zoom call with Dean of Students Christina Olstad. Along with several other members of the UW BIPOC Coalition and Associated Students of Madison student council, Bennett hoped to discuss the COVID-19 Student Relief Fund — a piece of ASM legislation designed to aid underrepresented students struggling financially due to the pandemic.

Olstad told Bennett and the others present that they were “disgraceful,” claiming their efforts were misleading students. Despite a strained admin-student relationship, the battle over financial aid persists along with the fight for other BIPOC student demands made in the wake of the reinvigorated Black Lives Matter movement in Madison.

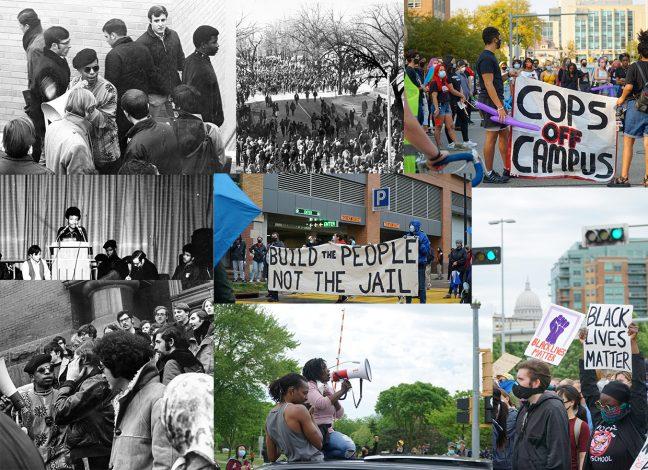

From the Black Student Strike of 1969 to the present-day social justice movement on campus, Black student protesters see their story at UW as one continuous fight that has shifted in form, but not cause.

As current students make a renewed call for the university to address the grievances of BIPOC students, protesters from 1969 and today reconcile their generational differences for that same cause — justice and equity for Black students on the UW campus.

Reckoning Racism on Campus

Despite the shockwaves it created in Madison at the time, the Black Student Strike of 1969 is not a well-known event among UW students. Launched amid a growing Black Power movement in the year following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., a group of students organized under the Black People’s Alliance to protest for a series of 13 demands.

The demands centered around recruitment of more minority students and faculty, the creation of a Black Studies department and other accountability initiatives for Black students to attain autonomy over matters relating to their UW experience and education.

Harvey Clay arrived on the UW campus in the fall of 1968 into the racial climate that would energize the strike. Recruited as a freshman football player from Texas, Clay came to UW on a football scholarship with hopes that he would find a more welcoming environment than the harsh discrimination he faced in the South. Clay said he soon realized his assumption was wrong.

“I found out it wasn’t that much different,” Clay said. “There wasn’t even a Black neighborhood in Madison at the time. There was no hot sauce. There was no barbecue. There was no cornbread. No iced tea. Getting a haircut was a big deal. I didn’t understand all that.”

One of the first times the discrimination on campus struck Clay was when Clay asked a football coach for help to plan his course schedule. The coach started to arrange his schedule without his input until Clay told him those classes would not work because he was pre-med. Because Clay would not take simple classes, the coach got mad and told him to “make his own damn schedule.”

Between football practices, Clay hung out with some of the white guys in the dorms. Clay said they always seemed nice to him — until politics got involved.

“As an athlete, I was okay. As a human being, comme ci comme ça … I wasn’t compliant because I expressed my opinion,” Clay said. “I was just supposed to shut up and play football.”

Hines said she experienced a similar culture shock when she arrived on campus to pursue law. Hines graduated from a historically Black college and was heavily active in civil rights protests in Mississippi. She said the tension boiling in Madison from the civil rights movement and anti-Vietnam War protests was the most familiar and welcoming part of campus to her.

Though Hines said she felt like an “odd-duck” swimming against the current as one of the few graduate students involved in the strike, she viewed her involvement in the strike as a “straight and clear” line to continue her advocacy.

“It just felt like what I was supposed to do, because I wasn’t in Mississippi anymore,” Hines said. “I was in Madison, Wisconsin, and it became clear that the same race issues that predominated in the racially segregated South … were issues in Wisconsin too.”

After Hines graduated from the UW Law School, she spent her life litigating various civil rights issues. She was eventually appointed to the bench of the Massachusetts Supreme Court, becoming the first Black woman to ever serve on the state’s highest court.

The climate on campus in the fall of 2020 echoed the tension felt on campus in 1969. Following the death of George Floyd, protests erupted across the nation in a recharged Black Lives Matter movement that called for sweeping systemic reforms. These protests reached the UW campus in August, heated by the police shooting of Jacob Blake close to home in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

While the headline-catching events sparked the flame for social justice movements in the fall, Bennett and fellow student Jordan Kennedy contend the movement had been building at UW long before.

Bennett said she felt isolated within her first few hours at the university as a freshman. As one of 60 students of color in the business school, Bennett said it was a “huge culture shock” to be a student of color in a sea of white faces.

When Bennett and other students of color in the Business Emerging Leaders Program — dedicated to bringing people of diverse backgrounds to the business school — were shuffled to the front of the class’s first group photo, she said her fears were realized.

“That was my first introduction to what it means to be a student of color here,” Bennett said. “It doesn’t matter if we feel welcomed, if we feel safe — it just matters that our faces are there to pretend that we’re being diverse.”

Kennedy said years of advocacy and controversy led to the current climate. In the fall of 2019, UW came under fire due to a Homecoming video that did not feature any students of color. The controversy caused campus-wide pushback, attracted national coverage and ignited the formation of the Student Inclusion Coalition, an organization dedicated to racial justice on campus. Still, Kennedy and Bennett said this summer’s protests revealed a glaring hole at UW that had not been filled.

Bennett said she always knew something was “missing” at UW, but had not known what to do about it. Out of this “missing” sentiment, the UW BIPOC Coalition formed. Kennedy, Bennett and several other students who met through the summer’s protests banded together to found the coalition. Their mission is to coalesce BIPOC students and multicultural student organizations to create a unified voice for actionable initiatives at UW.

Unified under 10 demands, the founders created a petition from years of outstanding propositions made by other campus advocacy groups such as SIC and the Wisconsin Black Student Union. Bennett and Kennedy said they believe the growing coalition sparks hope to overcome what they see as an even larger obstacle — ending inaction from the administration.

“I’m not leaving this campus until something changes, and now, every single one of us in the BIPOC Coalition thinks the same thing,” Bennett said. “I know that we’re not going to stop. We’re not going to stop fighting.”

Rising to Resistance

Through a flurry of protests over a few weeks in February of 1969, the Black Student Strike leaders held education rallies, marched down State Street to the Capitol, boycotted classes, disrupted lecture halls and closed off campus building entrances, according to a UW project created in partnership with The Black Voice and the Black Cultural Center.

But as protesters amassed in numbers with each demonstration, the response from the university and state government became more volatile.

A self-declared “foot soldier” of the strike, Hines said strike leaders would pack into a tiny house on campus to plan their moves. Clay and Hines said the protests manifested in various ways, though strike leaders had to quickly change tactics once they had started.

Two thousand students gathered to burn an effigy dummy entitled “UW Administration” on the lap of the Abraham Lincoln statue, according to the UW news site. The next day, 1,500 students blockaded the doors of Bascom Hall, where they were met by Dane County and Capitol police officers dressed in riot gear. As the protesters continually overcame police, Wisconsin Gov. Warren Knowles called in the National Guard.

At one of the protests, Clay said he stepped between female students and white male counter protesters — including some of his teammates on the football team. Standing in between the white students and Black protesters at nearly seven feet tall, Clay said he became a target when the Capitol police arrived. The officers beat Clay to the ground, breaking his glasses and hitting his head with a riot stick.

“They cracked my head open,” Clay said. “I just felt abused with no way to resolve it.”

Clay was one of at least two dozen students arrested by campus and Madison area police during the strike, according to the UW news site. While police met the 1969 protests with physical violence, the university more subtly undermined the students’ efforts.

About two-thirds of the university faculty signed a petition in support of the administration’s stance against the strike, according to the UW news site. In a UW Oral History Clip, Agricultural Economics professor C. William Loomer, who was on the Faculty Senate, said the university engaged in a lot of “petty” things during that time.

According to Loomer’s account, they used Senate rules and niceties to exclude students from meetings. Loomer said faculty members also chastised and tried to shut down students for how they represented themselves in the meetings, including bringing up their chosen attire or the number of students they brought to speak.

“What we were doing was playing games, to some extent … There were enough people in the faculty who were disgusted with the whole thing and didn’t want to listen to any students,” Loomer said in the UW recording.

While the strike lost some momentum and had a short moratorium on demonstrations, students reengaged with a short but destructive protest Feb. 27, according to the UW news site. UW administrators met the next week, and on March 3 they met one of the 13 demands to create a Black Studies Department.

Though this is considered the end of the strike, the participants continued to endure the impacts of the protests. Clay said the football staff carried disdain for his activism — coupled with his suffering academics, Clay lost his football scholarship and had to leave the university.

“I was no different than a stud horse. I was used to make the university money for playing football. End of story. End of usage,” Clay said. “I was there as a chattel-type animal to provide them income. Not to get an education, not to improve my life … unless I was going to do it through football. The fact that I wasn’t compliant with that, they didn’t have a bunch of emotion about taking my scholarship.”

Today, students in the BIPOC Coalition continue the fight for the unmet demands from the 1969 Black Student Strike. One of their 10 demands is for the university to reopen discussion on how they can honor the 1969 demands.

If not for the pandemic, Bennett said she believes the current campus climate would have been a repeat of 1969, given that students are still calling for some of the same changes Black Student Strike protesters advocated for five decades earlier.

Since the BIPOC Coalition’s creation six months ago, The university has met one of their demands, to remove Chamberlin Rock, a campus monument that once had a racist name. Bennett said the BIPOC Coalition has also gained traction in other ways, and they secured two meetings per semester with Chancellor Rebecca Blank mid-fall after advocating for months to get on her schedule.

Despite some wins, Bennett and Kennedy said the university has not budged on several demands, such as the removal of the Abraham Lincoln statue on Bascom Hill. Increasingly, the BIPOC Coalition leaders said the university is working against students’ efforts to advocate for their demands.

Bennett said working with the university is “traumatizing” and “exhausting.” Despite the research and time they put into ideas, Bennett and Kennedy said students are constantly gaslit and shot down during meetings.

“It’s not that we think we’re always right. It’s not that we think all our ideas should be implemented,” Kennedy said. “It’s that everything we bring up is rejected, pushed back, deterred and fought. It is never encouraged, revised, uplifted or anything of that nature.”

Bennett and Kennedy also said the university has refused to meet with student representatives following tense back-and-forths about COVID-19 relief for financially disadvantaged students. In an email to student leaders obtained by The Badger Herald, Olstad said all meetings would take place under a new set of rules, including a caveat that meetings would end if individuals engaged in “disrespectful and inappropriate behavior.”

In an email statement in response to these claims, UW Communications Director Meredith McGlone said campus leaders held meetings and corresponded with ASM and BIPOC Coalition members over the past few months in a “good-faith effort” to work together on emergency financial support.

She said student leaders’ unwillingness to consider alternative routes outside the original proposal after campus leaders raised concerns about its legality have made it “difficult to have productive conversations.” McGlone said they hope the dynamic changes in the future, and in the meantime are focusing on getting relief to students with readily-available funding.

While disagreements are inevitable, Kennedy said the “difficult environment” the university has created has existed long before the COVID-19 Relief Fund. Kennedy said it is the administration’s job to speak with students — by pushing them off, he said they are upholding their legacy of pacifying students of color.

“We’ve continued to go through this cycle and that’s due to … administration actively deterring, actively pacifying, bringing things down to compromises and silencing the strongest voices,” Kennedy said.

Rebuilding Relationships

McGlone said in her statement that while the university has made progress on many of the concerns raised in ‘69, they have not accomplished everything they need to do. McGlone said the university has recognized the participants of the strike by producing the award-winning UW news site, inviting participants back to campus to share their experience and welcoming strike participant John Felder as the 2020 Fall Commencement alumni speaker.

The College of Letters & Science will also formally recognize the contributions of student activists that led to the establishment of the Department of Afro-American Studies during the 2021 Spring Commencement.

“We hear the frustration and pain that current and former students are expressing and that inspires us with a sense of urgency,” McGlone said in the statement. “Our path forward is being forged every day by faculty, staff and students across campus who are working to make meaningful and lasting change.”

After UW revoked his scholarship, Clay took classes at the University of Hartford and Antioch University New England, where he eventually obtained his degree. Today, he owns Real BBQ and More in Louisiana, which was named the 26th best BBQ restaurant in the country by Yelp reviewers.

Clay said he constantly carries the scars of the strike and years of discrimination with him. Still taken aback by the racism he sees around him, Clay said he grows angrier as time passes. He struggles to explain the persisting inequities in America to his grandchildren, unconvinced white America’s heart will ever grow big enough to envelop and accept Black America.

“The difference between Black Lives Matter and what happened in the ‘69 protest [can be] compared to the storming of the White House on [Jan. 6],” Clay said. “Can you imagine what they would have been like had they been Black people? Murder. Hundreds of bodies dead … And that’s the difference from the dichotomy of where are we versus where we should be.”

Reflecting on her experience litigating civil rights issues and the current Black Lives Matter movement, Hines said racial issues are “never solved” — they “reinvent themselves.”

While she does not keep up with all the latest news at UW, Hines said students must stay vigilant and committed to the fight in order to not lose momentum from this summer’s protests.

“I always make the distinction between progress and change. There’s change, but not necessarily progress,” Hines said. “Things have changed [at UW] I’m sure since 1968, but as these new demands seem to suggest, that’s not necessarily progress, and it just reinforces the constancy of the struggle and the need for vigilance.”

When it comes to making progress at UW, Clay said he believes the university continues to prioritize monetary gain over the lives and welfare of students. Bennett and Kennedy said the university has demonstrated its willingness to put profit over students time and time again.

Bennett said the university has pushed aside key demands, like the removal of the Lincoln statue, and student activists have been told it is non-negotiable because of other university stakeholders. Bennett, Kennedy and Clay agreed the university needs to reconcile its roots as a predominantly white institution and how that plays a role in their monetary motivations.

“I think you still have a majority [of] older white men running the university like they always had and so they want to play to cater, but they don’t want to change because they got to give up some of the income,” Clay said.

Another major concern Clay, Bennett and Kennedy brought up was the persisting lack of diversity and UW’s failure to recruit students and faculty of color.

In 1974, early race and ethnicity data indicated that 2% of UW students were Black, according to the UW news site. Preliminary data from 2020 shows that 2.19% of students identify as Black — less than a .2% increase in over nearly half a century. The 1969 and the 2020 demands both call for increased efforts in this area.

In her statement to The Badger Herald, McGlone said increasing student and faculty diversity remains an integral part of UW’s mission to improve the experience of students of color on campus. While progress “may feel slow,” McGlone said the university is encouraged by the nearly 20% increase in students of color who entered UW in the fall of 2020.

Additional initiatives like Bucky’s Tuition Promise, the Target of Opportunity Program, the PEOPLE program and the Mercile J. Lee Scholars Program all contribute to the university’s efforts to increase diversity, McGlone said.

To fix the errors he experienced first-hand in the past, Clay said the university must examine “every facet” — including where students come from, their educational background and fiscal resources — to level the academic and social playing field at UW.

In addition to implementing their demands, Bennett and Kennedy said student leaders hope to regain autonomy that they believe was lost due to shared governance statute changes in Act 55. Bennett and Kennedy said the BIPOC Coalition will not fold to administrators, though they believe that invoking a higher shared governance standard will empower the student voice and pave the way for necessary structural changes.

Looking toward a brighter future, the two generations of Black leaders on the UW campus shared the same somber sentiment — the fight must go on.

“I don’t think that [students] should measure success by necessarily getting everything you want. Although you will continue to struggle for that, you decide that you’re going to be on the side of justice,” Hines said. “That’s the message that I would give: wherever you are, do what you can, because that’s what it’s going to take.”