When asked which food industries represent Wisconsin, anyone will jump to “beer and cheese,” with maybe sausage and sauerkraut for good measure. There is, however, a reason those foods come up together, beyond the fact that they make a great meal: They all fall under a category of fermented foods and beverages, one that James Steele, a food science professor at the University of Wisconsin, teaches across the board.

Steele has taught labs in brewing and cheese making, including this semester’s Food Science 375: Fermented Foods and Beverages, where students learn firsthand the science behind the drinks and snacks. While the end products are vastly different, the process in creating them is essentially the same.

“The similarities between dairy and brewing are huge,” Steele said. “We’re talking about the same concerns, from the front end to the back of all these foods. The skillsets people need to work in these various industries are very similar.”

Wisconsin has long been a haven for such fermented foods, yet it may come as a surprise that the state is also the world’s largest producer of soy sauce. Soy sauce, too, is fermented, meaning that it is much closer to beer, cheese and yogurt than many would like to think. As an example of the similarities among fermented foods, Steele compared mozzarella cheese to a dark porter.

“Mozzarella cheese browns when it cooks, and too much of that is a bad thing,” Steele said. “That same reaction occurs in the malting step of beer brewing and gives rise to the brown colors in darker beers.”

Not only does the browning reaction provide the color, it also plays a significant role in the beer’s flavor. The amount of browning to the grain can determine what type of beer comes out down the line. The same reaction has different results in different foods.

According to Steele, the brewing process, from start to finish, goes something like this: Barley is steeped in water to cause germination and production of enzymes that produce sugars from starch and amino acids from proteins. Later, the grains are dried at high temperatures to cause a reaction that creates brown pigments and a large variety of flavors. This is where creativity can come into play; altering the conditions of this reaction can result in a host of different pigments and flavors and, hence, vastly different beers.

The next step is to add more grain and water, which all becomes yeast food. Then, you add hops to the yeast food, boil the yeast food to sterilize it and add yeast to ferment it. The brewer makes the yeast food, the yeast makes the beer and that is the essence of beer brewing.

While a beer-brewing class may sound exciting to any Badger, the delicate process requires a heavy background of scientific knowledge from the students. The class brings together microbiologists, chemical engineers and food science students, each of which contribute their own valuable skill sets. In addition to the lecture, a laboratory section is planned for next year to give students a hands-on, applied science class with potentially delicious results.

“[In the Food Sciences Department], we know what food processing is like,” Steele said. “Whether it be dairy processing courses, or candy courses or meat processing, it’s all applied science to us.”

Aside from the scientific prerequisites, the class will have an age stipulation as well: Students must be 21 to enroll.

“The trained students will have to be able to pick up the subtle flavors in hops, in malts, and the only way to do that is to taste the beer,” Steele said. “If you’re not 21, you can’t taste the beer, and you just can’t learn the same things.”

Tasting the beer along the way will become all the more important near the end of the semester, when students will present their home brews to a panel of experts, including David Ryder, the vice president of brewing research at MillerCoors, who is also known as the head brewmaster.

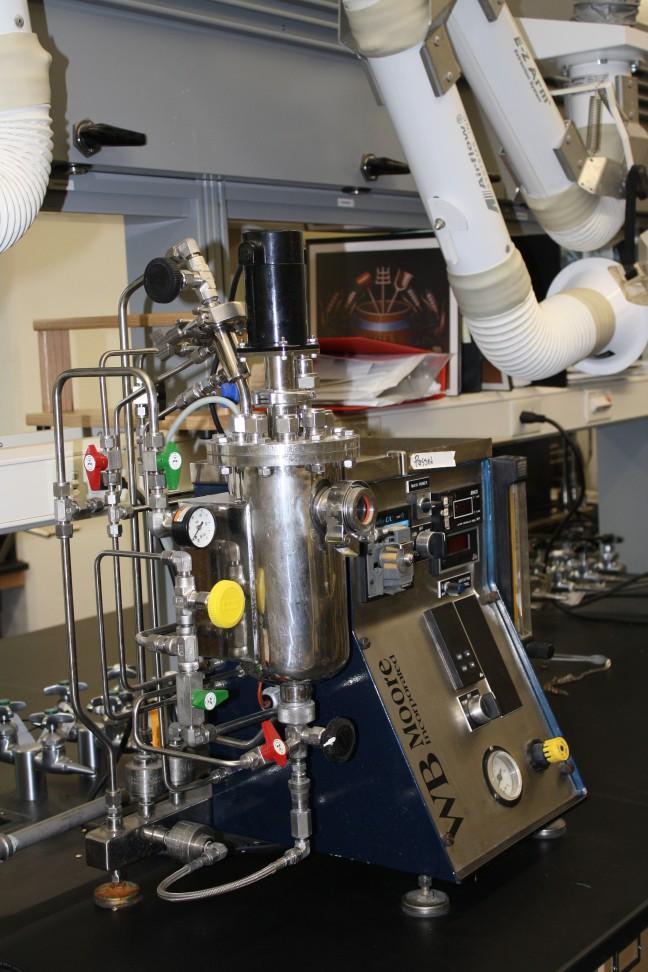

Ryder and MillerCoors actually made the UW program possible by donating more than $100,000 of brewing equipment and fermenters to the university in 2008. The brew lab, currently housed in the Department of Bacteriology, is a small replica of the exact same equipment MillerCoors uses on a massive scale.

And although by now the cost of equipment donated approaches $250,000, further expansion will be necessary to achieve the goals of Steele and the food science department. Steele is developing a fermented foods and beverages certificate program, a program he hopes will be the first step toward a larger brewing facility. With a larger facility, Steele hopes that more students could learn the science and the craft, all while producing large-scale brews to sell on campus.

“Even when we get this MillerCoors stuff here in Babcock Hall, that’s not a scale that we’d even be able to brew for the Memorial Union here on campus,” Steele said.

The revenue from beer sales would help fund the certificate program and the fermented foods classes, perhaps even creating a self-sustaining program. It has been done before, as Steele noted, at the Babcock Dairy Plant, which produces much of the ice cream and cheese found around campus.

“Many of our students work in the dairy industry now in Babcock Hall. That’s a phenomenal opportunity for students to develop those skill sets in an industry,” Steele said. “I’d like to be able to offer the same thing from the brewing side.”

Moreover, having a brewery on campus would allow interested students to learn about the brewing industry firsthand, rather than doing short internships with larger companies.

“And what a cool way to teach science!” Steele said. “For me, it’s one of the greatest things, and I’ve taught science for a long time. … But now you’ve got the opportunity to teach great science in a venue where you have students’ attention, and that doesn’t get a lot better than teaching beer.”

Should all go as planned, Steele already has a vision of the flagship brew: “Bucky’s Red Lager.”

“That would be the fun part – to make something good that represents the university well,” Steele said. “We want to make artisan products that have great flavor, that are value-added, that are providing people jobs … and I think we have a compelling story to go with it.”